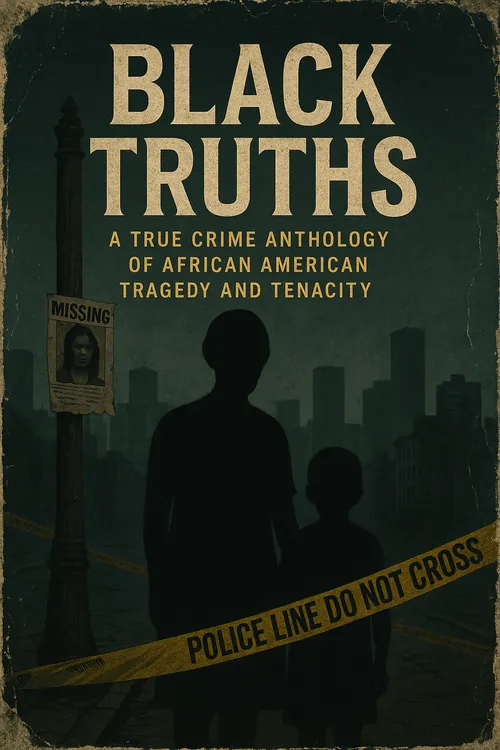

Prologue: Missing but Not Missed

In Chicago’s South and West Sides, boys vanish.

Not in crowds. Not in headlines.

But slowly, quietly, until no one asks where they went.

The stories rarely make national news.

There are no vigils with candle-lit white balloons, no urgent press conferences.

Just grieving mothers, cold police files, and the eerie sense that some children are not meant to be remembered.

In this chapter, we explore a string of unsolved disappearances and suspicious deaths involving Black teenage boys in Chicago—cases that remain open, ignored, or forgotten.

Case #1: Terrance “Terry” Jackson – Age 15

Last seen: September 6, 1998

Neighborhood: Roseland

Status: Missing. Case cold.

Terry was walking home from basketball practice at his high school when he disappeared. He texted his older brother saying he was on the way. He never arrived.

His family reported him missing within 12 hours. Police told them to wait.

“They said he probably ran away. But Terry had no history of trouble. He had a game the next day.”

— Tasha Jackson, mother

It would take three days for the search to begin. By then, the trail was cold. Surveillance cameras in the neighborhood were broken. No witnesses came forward.

Terry’s name was barely mentioned in the local press.

No Amber Alert was ever issued.

Case #2: Darnell Petty – Age 14

Last seen: December 13, 2002

Neighborhood: Englewood

Status: Found deceased. Cause: Undetermined.

Darnell was found frozen beneath a viaduct, his body curled near a concrete wall. He had no shoes. His coat was zipped, but blood was crusted near his nose.

The medical examiner listed the cause as "exposure to the elements."

His mother believed otherwise.

“That’s how they bury our boys—by calling them accidents.”

Darnell had no history of running away. He was last seen getting off a city bus two blocks from home. The driver remembered him. But what happened in those minutes after remains unknown.

Case #3: Myles Washington – Age 16

Last seen: May 21, 2007

Neighborhood: Austin

Status: Missing. Case reopened in 2021.

Myles disappeared on his way to a friend’s house. His phone was found in an alley. Weeks later, an anonymous tip claimed he had been taken by an older gang member for debt retribution. But the claim was never verified.

In 2021, after national scrutiny of cold cases involving Black teens, Myles' file was reopened by the Illinois Attorney General’s Cold Case Unit. DNA from under a fingernail on his phone case is now being processed.

His mother, Danika Washington, continues to search.

“Every day I wake up hoping I’ll find my son. And every night I go to bed with nothing but silence.”

Pattern or Coincidence?

Between 1995 and 2010, over 300 Black teens went missing in Chicago, many from neighborhoods already plagued by violence and under-policing. Most were boys between the ages of 13 and 18.

Though some were found, often deceased, dozens remain missing. A troubling number of cases were initially dismissed as runaways, despite family protests.

Key systemic issues:

- Delayed search efforts

- Lack of Amber Alerts due to age and “runaway assumptions”

- Inconsistent reporting in local media

- Police disinterest in youth labeled as “at risk”

Community leaders argue that if the missing teens were white and from Lincoln Park or the Gold Coast, the city would have shut down to find them.

Ignored by the System

Chicago mother and activist Renee Barnes, who formed the group “Mothers for the Missing”, says the city continues to fail Black families:

“We live in a world where you can disappear, and if your skin is brown, nobody notices. You’re not a headline. You’re not a priority.”

Renee’s own son, Corey Barnes, vanished in 2005. His case has been reopened three times—with no resolution.

Recent Efforts and Renewed Hope

In 2020, under pressure from activists, the Chicago Police Department created a Special Victims Unit focused on missing minors.

In 2023, the city launched the Missing Youth of Color Task Force, aimed at increasing media exposure and resource allocation.

Yet most families say real change is still slow.

Legacy: Lost and Waiting

These boys had dreams—of college, music, basketball, becoming fathers, becoming more. But the world never gave them the chance.

They are not footnotes.

They are not runaways.

They are sons, brothers, futures.

They are the Lost Boys of Chicago.

And they deserve to be found, remembered, and fought for.

“You don’t need a headline to matter. But you shouldn’t have to die in silence.”

— Community advocate, 2022 vigil

This story has not been rated yet. Login to review this story.