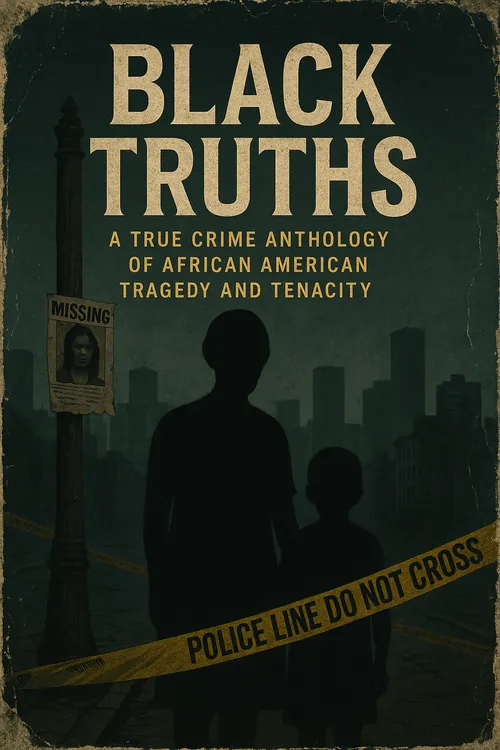

Prologue: “It’s Happening Again”

On July 28, 1979, in Atlanta, Georgia, two young boys—Edward Hope Smith (14) and Alfred Evans (13)—disappeared. Their bodies were found days apart in a wooded area off Niskey Lake Road. One had been shot. The other was strangled.

A local Black resident whispered to reporters:

“It’s happening again.”

But few in power listened—because the children were Black, poor, and from the "wrong" neighborhoods.

Over the next two years, at least 29 Black children, teens, and young adults would be murdered. Atlanta was paralyzed by fear, but the nation's attention came late. And the final truth about what happened remains unclear to this day.

The Early Murders: A Pattern Emerges

At first, the disappearances didn’t seem connected.

July 1979: Edward Smith and Alfred Evans

October 1979: Yusuf Bell (9), last seen running an errand for a neighbor

March 1980: Eric Middlebrooks (14), found bludgeoned behind a bar

One case bled into the next, but police and city leaders offered little more than reassurances. Atlanta, a city still glowing in the aftermath of electing its first Black mayor, Maynard Jackson, was reluctant to admit a serial predator might be targeting the most vulnerable.

For months, parents cried foul. Mothers marched. Clergy prayed. Local Black journalists warned the city was under siege. But national media coverage was almost nonexistent. There was no Amber Alert system. No CNN updates. Just flyers stapled to telephone poles.

Fear and Frustration

The disappearances continued:

May 1980: Latonya Wilson (7) taken from her home while her family slept.

June 1980: Anthony Carter (9) found stabbed.

September 1980: Clifford Jones (13), found strangled behind a dumpster.

Many of the children were last seen near public transportation stops or walking alone through familiar neighborhoods. Most were boys. Most were from Southwest Atlanta—the heart of the Black working class.

The Black community was not just grieving; it was unraveling.

“We were watching our babies vanish one by one,” said activist Xernona Clayton.

“And no one with power seemed to care until we made them.”

Public Pressure and the FBI’s Arrival:

By early 1981, as the body count grew, so did the public outcry.

Jesse Jackson, national civil rights leaders, and local ministers demanded federal help. The FBI joined the case, launching a multi-agency task force.

City leaders imposed curfews. Patrols increased. Still, the killings continued.

It wasn’t until May 1981, when authorities began staking out bridges at night—believing the killer might be dumping bodies in rivers—that a break came.

A Suspect in the Night: Wayne Williams

In the early hours of May 22, 1981, officers heard a splash under the James Jackson Parkway Bridge. They stopped a car crossing shortly after. The driver was a 23-year-old freelance photographer and music promoter named Wayne Bertram Williams.

He was oddly composed, claiming he was scouting talent. But two days later, the body of Nathaniel Cater (27) was found downstream.

Williams quickly became the prime suspect.

Over the next two months, the FBI placed him under surveillance. Fibers found on victims matched those from Williams’ home, dog, and car. He was arrested on June 21, 1981, and charged with the murders of Cater and Jimmy Ray Payne.

The Trial and Controversy:

Williams was convicted in 1982 for those two adult murders. Afterward, police closed 22 of the child murder cases, attributing them to Williams based on “pattern evidence.”

But there was no trial for the children.

No jury heard their stories.

And the evidence in many cases remained murky, circumstantial, or nonexistent.

Doubt and Division:

To this day, many do not believe Wayne Williams killed all—or even most—of the children.

Some parents of victims say police ignored alternative leads.

Some activists believe multiple killers were involved.

Former investigators have claimed police closed cases prematurely to ease public panic.

A 2019 HBO documentary series, Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered: The Lost Children, reignited public interest. That same year, Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms and Police Chief Erika Shields reopened the case to retest evidence using modern forensic technology.

As of 2025, the results remain inconclusive.

The Children Left Behind

Names etched in silence:

Angel Lenair, age 12

Lubie Geter, age 14

Joseph Bell, age 15

Patrick Baltazar, age 11

Terry Pue, age 15

…and so many more.

There are no statues in their memory. No school curriculums that teach their stories. Just grieving families, aging case files, and unanswered questions.

Legacy: The Shame in the Silence

The Atlanta Child Murders taught America a painful lesson:

Black children could vanish—and it might take years before anyone listened.

“We knew something dark was happening. But we were screaming into a void,”

— Camille Bell, mother of Yusuf Bell

The tragedy shook a generation. It also set a precedent: grassroots activism in Black communities would no longer wait for institutional permission to cry foul. It gave rise to organizations like the Black and Missing Foundation, determined to keep these stories alive.

Postscript: Still Searching

To this day, Wayne Williams maintains his innocence.

Some believe he is guilty of some murders but not all.

Others believe justice has yet to be served.

Either way, the children deserve more than theories.

They deserve the truth.

This story has not been rated yet. Login to review this story.