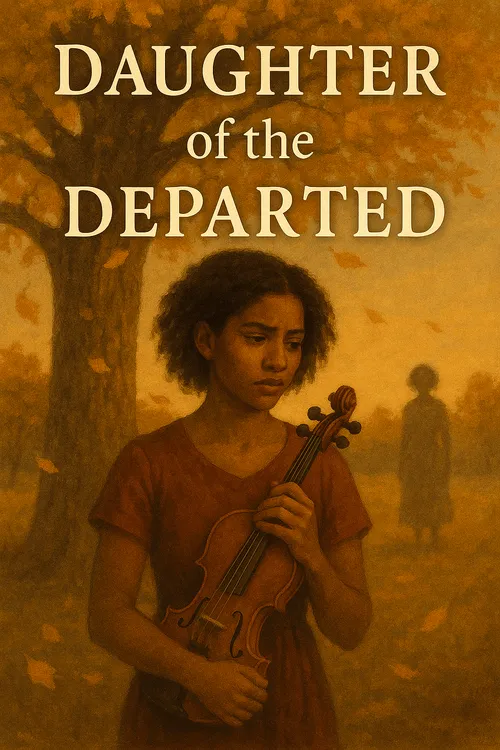

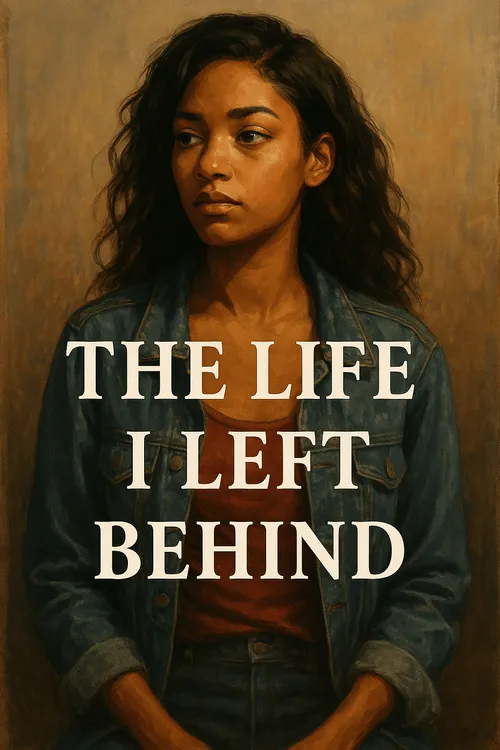

The last time Marisol saw her mother, she was five years old.

She remembered the clink of keys in her mother’s hand, the slow drag of a red suitcase across the cracked kitchen tile, and the promise that hung in the air like a lie:

“I’ll be back, baby. You be good for Daddy, okay?”

Marisol nodded, tiny arms clutching a threadbare stuffed bear to her chest. She didn’t cry—not until the front door shut, and the silence swallowed everything.

That silence would become her oldest memory, her first teacher. It told her how to behave, how not to ask too many questions, how to tuck pain into the corners of her body where no one could see it. Her daddy tried. He really did. He poured cereal into bowls with shaking hands and burned grilled cheese sandwiches because he was used to wielding wrenches, not spatulas. He braided her hair too tight and forgot school picture days. But he never left.

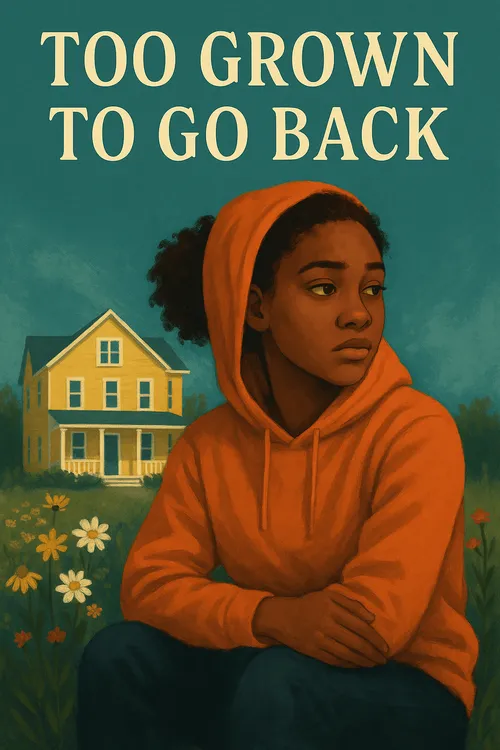

She sat on the porch every Saturday for months after her mama disappeared. Waited until the sky turned orange and the porch light clicked on, drawing bugs to its glow like broken promises. She always believed this would be the day her mama’s rusted green Nissan would pull into the driveway. Always hoped to see her leaning out the window, arms open wide, saying “See? I told you I’d come back.”

But she never did.

And slowly, Marisol stopped waiting. The porch became just a porch again. The silence stopped being a question and settled into a fact.

Years later, when people asked her about her mother, she would shrug and say, “She left when I was little.”

What she meant was: She never looked back.

Her daddy was a good man. Not perfect, not always patient, but good in the way that mattered—he stayed.

His name was Ernesto, but everyone called him Ernie. He worked long hours at the mechanic shop on 4th and Monroe, coming home with hands stained in oil and a back that ached so bad he sometimes had to lie flat on the living room floor to stretch it out. Still, he never let Marisol go to bed without brushing her teeth or saying goodnight. Some nights, when the world felt too big for her tiny chest, he would carry her to bed in his arms, humming off-key to old Ritchie Valens songs.

He didn’t talk much about her mama after she left. Didn’t say her name. But sometimes, when he thought Marisol was asleep, she’d hear him through the thin apartment walls—soft curses, the pop of a beer can, and a sigh that sounded like his ribs were caving in.

He never dated seriously. There were women here and there—some nice, some not—but none who stayed long. Marisol never asked why. Maybe he was waiting for her mother to come back too, even if he’d never say it out loud.

He didn’t always get things right. He missed parent-teacher conferences. He didn’t know how to braid hair without pulling too tight. And when he was angry, he yelled with a voice that filled the whole apartment like thunder in a tin can.

But he tried. Every single day, he tried.

That, more than anything, became Marisol’s measure of love—not flowers or sweet words, but showing up, even when it was hard. Even when your hands were cracked and your heart was tired.

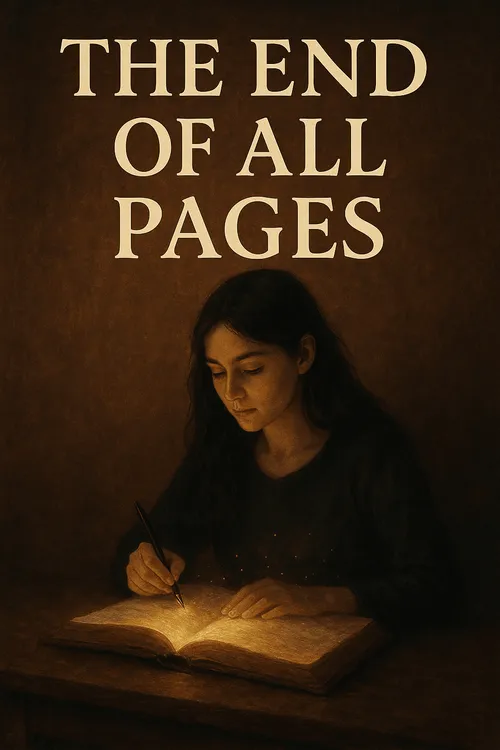

Marisol couldn’t sleep. The hallway light crept under her door like a strip of gold, and her room felt too quiet, too full. She lay still at first, hoping sleep would come, but the questions stirred again. The same ones that came every now and then, like old ghosts.

Why did she leave? Did she miss me? Was I not enough?

She slipped out of bed, bare feet on cool floor, and padded down the hall. Her father sat at the kitchen table, a faded Dodgers cap turned backward on his head, his fingers wrapped around a pen as he hunched over a stack of bills. There was a half-empty beer can by his elbow and a tired crease between his brows that never seemed to fade.

He looked up, surprised. “What are you doing awake, mija?”

She shrugged. “I had a bad dream.”

He didn’t ask what it was about. He didn’t need to.

“Come here,” he said softly, pushing the papers aside. “Sit with me.”

She climbed into his lap, her legs folding against his, head resting under his chin. He smelled like motor oil and Ivory soap. His hand rubbed gentle circles on her back.

“You ever think about Mama?” she asked, the words so small she barely heard them herself.

His hand slowed. “Sometimes,” he said after a long pause. “But mostly, I think about you.”

“Do you think she’ll come back?”

He kissed the top of her head. “Maybe. Maybe not. But I’m here. I always will be.”

That night, he carried her back to bed and stayed until she fell asleep, his calloused hand resting lightly on her back. Marisol never told him, but she didn’t have a bad dream. Not really. She just needed to hear it again—that someone had chosen to stay.

This story has not been rated yet. Login to review this story.