Among our hierarchy of fears, being alone and lost in the dark ranks near the top of most lists. To Prentice Foley, who was very much alone and lost in the dark, it overshadowed all of his other fears—the fear of being annihilated, of evaporating, of vaporizing without a trace; it cut to his soul.

To make the situation even more frustrating, the route he was taking was a familiar one. He’d driven it before: A straight shot north up the interstate, an exit at the 201 mile marker, then another twenty minutes on a county two-lane to the rural community of Grass Lake where his family had spent vacation weeks every summer when he was a child. According to the map that Father Ted had drawn, just beyond the lake itself a road called Ward veered off, and a quarter mile further, Pure Heart of Mary Catholic Church stood. Prentice was pretty certain that Pure Heart of Mary was the church he had attended on each vacation Sunday when he was young, since for the Foley family, going to mass was non-negotiable no matter where you were.

The whole trip should have taken under two hours and Prentice was comfortable making it, even under threatful skies; that’s why he’d volunteered to pick up Father Bartolomeo himself. Father Bartolomeo was the pastor of Pure Heart of Mary, but he was about to begin a month as guest pastor at St. Aloysius while Father Ted was in Haiti. Prentice was happy to play chauffeur. It got him out of the house for half a day and made him feel he was giving something back to Father Ted who, over the years, had offered him much guidance and empathy.

The trouble had begun—as he saw it—when Father Ted insisted that he take the parish Escalade, which had every luxury amenity imaginable except for a functioning GPS system. Prentice’s own Chevy may have had a screaming fan belt and two hundred thousand miles on the odometer, but he’d made sure to equip it with a state-of-the-art Garmin. Prentice knew it was a sin to compare a GPS with the Bible, but as tools for direction, he had come to view both as indispensable.

“Father Bartolomeo is a trifle overweight,” Father Ted had pointed out delicately. “He appreciates God’s bounty and he’ll appreciate the roomier ride. Honestly, Prentice, so will you. Besides, why should you put extra miles on your personal vehicle for a church mission?”

Father Ted was his friend and spiritual advisor, and he was well acquainted with Prentice’s grocery-getter. It was, perhaps, his saccharine way of suggesting that the old car might not be up to the job. Father Ted was a saccharine fellow through and through—that’s one of the things Prentice appreciated about him; his sugar-white hair which even extended to his eyelashes and the fine hairs on his hands. Often, when bathed in the light that trickled in through the lancet stained glass windows of St. Aloysius, he looked like he was covered in frost.

Father Ted understood that Prentice was struggling to keep his head above water with the forty-two thousand dollars the state paid him to teach history to middle-schoolers and a wife who would rather watch birds and play Words with Friends with strangers than accept even part-time work. Like Prentice, Maribell had been an only child, but unlike him, she had not been hustled off to Catholic boarding school at the age of six; she’d been doted upon by the couple who had adopted her.

Nice childhood if you can get it, Prentice thought, but the consequence—again, as he saw it—was that Maribell felt entitled. She believed she was too smart to be trapped inside who she was, yet showed no inclination to pursue higher education or a challenging career. Maribell was perfectly content with intellectual hobbies she could switch on and off at her leisure. Father Ted knew about Maribell, too—he’d introduced them, then married them at St. Aloysius Church and counseled them when Maribell’s birth mother tried to contact her. In general, Father Ted was a font of succor in Prentice’s world; he knew about the Chevy’s fan belt, knew about the snarky, ungrateful ninth graders, knew about the half-decade of serial abuse that Prentice had suffered at the boarding school. But in spite of all the support and camaraderie, there were still things that Prentice was too ashamed to tell him, and his childlike fear of being alone and lost in the dark was among them.

The trouble that began with the Escalade compounded exponentially when Prentice found that the two-lane to Grass Lake was closed for resurfacing. The nasally whine of warning tones rose from behemoth equipment just cresting the hills in the distance. Detour signs pointed to an unfamiliar side road, so he took it. Taking directions was among his core competencies. After two miles, the pavement ended and the road became ungraded dirt. That didn’t seem right, and he was grateful for his phone, but when he pulled into the mouth of a farm lane that led to soggy, empty acres of fallow field, he could not drum up a signal. There was a lonely-looking ranch house at the end of the lane, but it looked abandoned, and even if it hadn’t been, he couldn’t imagine what he’d have asked the owner. The detour signs were well-marked despite the deterioration of the road. But after another few miles, the signs petered out and the farmland on either side of of the car gave over to fields of jack pine that gradually evolved into a thick hedge of hardwood forest.

As the road narrowed, clouds lowered and a steady drumbeat rain set in. He kept an eye on the clock, but this did not keep the minutes from passing. He soon saw that his timing was shot—the plan had been for him to return to St. Aloysius with Father Bartolomeo before dark, and now, with night clamping down and the storm intensifying, he had no idea where he was. Trees became wraith-white in the headlights and angry water roared in trenches on either side of him; he could hear the sound right through the Escalade’s luxury insulation.

Potholes soon filled with black muck; he slowed the vehicle to a crawl to avoid a bottom-out. As spooked as he was, he was keenly aware that the vehicle he was driving belonged to someone else. He had sincere respect for the possessions of others—he’d learned that much growing up in a dormitory with thirty other boys. He soldiered on; time did as well. The drone of the windshield wipers became oppressive and the radio might have helped, but that would have required him to stop and figure out how it worked. And there was no place to stop. Given an opportunity—anywhere to safely maneuver the gigantic car—he would have turned around and headed back to the happy land of cell phone towers and blacktop highways, of lights and mundane familiarity, of teenagers making fun of him and wives complaining about expired condiments in the refrigerator, but the forest became thicker and the occasional two-tracks that pierced the dark trees were blocked by wooden barriers or swinging metal gates.

By that point, the road was no longer wide enough for two SUVs to pass without clipping an outside mirror, and he had no idea what he’d do if he encountered one—and then he realized then that he had not seen a single other vehicle since the detour, coming, going, or parked at a trail head. That made trying to negotiate a turnaround even more out of the question, because he imagined that if there was anything worse than being alone and lost in the dark, it was also being stuck half-submerged in a drainage ditch.

To offset his swelling paranoia, he tried to focus on other things. Drive and think, he ordered himself; don’t dwell. And yet his life was somewhat limited, and his thoughts returned to Father Ted, whose insistence on taking the Garmin-less gas-hog had prevented him from mapping another route. Even the next exit would have brought him to Grass Lake from the north, forty minutes out of his way perhaps, but this detour was a disaster with no end in sight.

Still, blaming the pastor years was incompatible with Prentice’s intrinsic faith in the authority of the church, and he avoided the temptation to do so, just as he had avoided laying the last seven years of frustrated flesh at the threshold of St. Aloysius. Seven years is how long it had been since the fateful meeting in the rectory his when Father Ted had dropped the bombshell about Maribell’s birth mother; the couple, then married two years, had left that meeting as white as a gibbous moons—although, as he was to discover in the weeks and months and years to come—her face remained several shades whiter than his.

Sex is an uncomfortable subject for most Catholics, and long ago Mother Church came up with a genius solution in order to keep herself a going concern: As long as sex was done for the purpose of procreation, it was sacred. And procreation was their mandate. Masturbation was a no-no—at his boarding school, they’d called it ‘flogging the bishop’. So was adultery and even lusting in the heart—an organ only a couple of phallus-lengths distant from the groin. But as long as intercourse was confined to matrimony, all your sequestered desires and nasty fantasies could be orgasmed out in the privacy of the marriage bed. And since neither Maribell nor he wanted to physically experiment and both wanted children, good old missionary-approved sex was adequate stimulation to quell the beast within. Maribell may have had her own tales of monsters hibernating restlessly—Prentice never asked and certainly never told her about his experience with potency of erections and semen at the hands, quite literally, of upper classmen at St. Benilde Preparatory Academy.

That was long ago and pushed as far beneath the surface as it would go. He married at twenty, and having secured a wholesome outlet for the sexual imperative, Prentice wanted to utilize it twice, sometimes three times a day; all, of course, with a goal no less lofty than making a baby. Maribell claimed to want this baby, too, and although two years into the outlet-utilization they still didn’t have one, it wasn’t until after the letter from her birth mother arrived that Prentice learned what she actually thought of the act required to create one: Not much.

The letter had been left in their mailbox un-postmarked on the occasion of Maribell’s 21st birthday and read:

Dearest Daughter: It has been twenty-one years since I last held you in my arms. Not an hour passes when I don’t think of you and wonder what you are doing. Whatever it may be, I hope you are being utterly worshiped. I hope that everyone who sees you falls in complete and total adoration with you. You are a miracle who I carried inside my belly for nine long months, and you will always be mine. I hope you will consent to meet me soon so that I can hold you to my bosom once again.

It was signed ‘Pollyanna Tiolek’ and it was so portentous that they’d taken it immediately to Father Ted and requested counsel. Father Ted was the right one to approach, since there was realpolitik behind his shepherding. He had contacts at the Catholic adoption agency who’d farmed Maribell out two decades earlier, and although her files were sealed, he knew the ecclesiastical sleight-of-hand through which he could unseal them.

Several days later, he asked the young couple to return to the rectory to share what he’d learned. It was not pleasant. He made sure they were seated and offered them some sacramental wine prior to explaining the matter even though it was only ten in the morning. It turned out that Pollyanna Tiolek was indeed Maribell’s biological mother; she’d come from an impoverished clan at the periphery of a diocese in Aberdeen County and had only been fourteen years old at the time of the birth. Father Ted folded his soft hands in front of them and stared at the way his fingers interlocked, wondering absently if this had been what inspired the fellow who invented the zipper. “Ah…’ he said softly. “It seems that she was impregnated by her own uncle.”

Prentice was sure that Maribell had been too sheltered and spoiled growing up to grasp the depths to which mankind’s deviancy could plumb. He, of course, was not. As a couple, they restricted their physical contact to darkened bedrooms, but now he felt a need to drape his left arm across her shoulders. She recoiled slightly, but did not remove his arm, although she might have had she realized that his gesture was less about empathy and more about patronizing smugness: Suddenly, both were faced with evidence that her smartest-person-in-the-room demeanor had its genetic origins in an act of incest

.

Father Ted took a sizable sip of his own tumbler of sacramental wine and said, “See, the thing is… Something else… I found out… I looked at the parish records of the family, and it seems that Pollyanna’s uncle is also your uncle, Prentice.”

He laid it out on the table with a diagram. The family tree was easily followed, and the blood connection, hitherto unknown, was undeniable. Now Maribell pried Prentice’s arm from her shoulders. “What does that mean?” she gasped.

“It means we’re cousins,” Prentice said and blinked at Father Ted. “Doesn’t it?”

“I’m afraid so. Now, I have given the matter a lot of thought before I asked you here. I’m sure you’ll need time to process this information. It’s distressing, I’ll admit. We can talk about annulment. I’ll have to juggle the Canons a bit, but under these circumstance—there’s no way you could have known you were related—I’m sure the diocesan tribunal will grant it. But it will require an explanation to your friends and family. And surely, others will find out. The busybodies from the Audubon Society. The ninth graders at school. But I can approach the bishop today if that’s you want.”

Prentice did not want—why should they bear any shame or embarrassment? They were victims, not sinners. Why should they pay a penalty? But Maribell looked as if she’d just learned that the Keto shakes she loved were made out of aborted Irish fetuses, so perhaps some processing was in order. For him, there were immediate questions.

“Are there alternatives?”

“In my opinion, yes,” answered Father Ted. “The best one. I can contact Pollyanna Tiolek and forbid her from contacting you again under legal penalty. And then, going forward, we three can claim to have had an enlightening experience in the science of coincidence and in God’s mysterious channels, whose workings we can never fully understand.”

“And then?” Prentice asked.

“And then, we can never, ever bring it up again.”

“But if Maribell and I remain together, wouldn’t children from such a union risk…” Prentice grappled for the right word. “Mutant-ness? Mutant-hood?”

Father Ted cleared his throat—it was a touchy subject that came up more often than he liked in chat forums between devout Christians and prurient doubters: “Remember, when God created Adam and Eve, He instructed them to go forth and multiply, and multiply they did. Thirty-three sons and twenty-three daughters. And those children all went forth themselves multiplied. Multiply all you want, but one plus one still equals two. Read between the lines here, if you will.”

So, Prentice read between the lines. Adam’s children must have had sexual congress with each other, meaning that we’re all the descendants of incest, and not between cousins, but between siblings. And God—who can do anything—chose to do nothing. Actually, He encouraged it. God was fine with it, and the more he thought about it, the more Prentice realized he himself was better than fine with it. Although he wouldn’t breath a word of such thoughts to Father Ted or Maribell, the idea of making physical love with a family member filled him with unaccountable excitement—thrills so strong that he was later compelled to confess them, although at a different church and to a priest who was not Father Ted.

This new bit of lechery would remain unfulfilled; Prentice’s outlet closed shop and swallowed the key. Maribell did not want her marriage annulled either, but only because explaining the reason to her adoptive parents was unthinkable. They utterly worshipped her; they completely and totally adored her. Father Ted assured them that the nature of the adoption had been such that they could not have known about Maribell’s genealogy, and they agreed that telling them now, in their later years, would be unspeakable cruel.

That morning, they had driven home in silence, shell-shocked and pole-axed, but since they had agreed not to mention it again, they did not—except for the once, that night, when she rejected his bedtime caress and said that the idea of intimacy with her own cousin made her physically ill—green meat, milk-and-mustard, finger-down-the-throat ill.

“God knew,” she said. “That’s why he didn’t already make us a baby. You gave it your best shot, pardner, but somebody in this room is shooting blanks. Now if God is so intent on me multiplying, He can pull another Immaculate Conception out of His hat.”

Prentice was sure that this was blasphemy, but he bit his tongue and hoped that the reproductive urge would become as irresistible in her as it was in him, but alas—that did not occur.

“Give her time,” frosty Father Ted had urged him, over and over again. “Be understanding.”

He’d obeyed, and in consequence, in seven years, there had been no divine intervention, no virgin birth ...and no sex.

Overhead, the trees formed an arch, and within the onslaught of the weather, the Escalade found a manic equilibrium. It bounced and swayed from rut to rut, pushing through savage sheets of rain and keeping up a monotonous pace. The wind—largely muted by the car’s armor—howled as it searched for a way inside, but as long as the sheet metal held, it remained at bay. More time passed—another half an hour—and it occurred to Prentice that this was a nightmare that might go on forever. Which would make it Hell. He racked his memory for a hint of what might have happened—had he died on the interstate in a roll-over or a head-on collision? Had there been no exit at 201 after all; no resurfacing project, no detour? He recalled the convoy of semi-trailers outside Mason, but he’d threaded through them… hadn’t he? And it didn’t seem likely that Hell would simply appear without a dramatic Final Judgment, or a cursory search for your name in the Book of Life, or Heaven’s gatekeeper tossing you a nasty farewell gesture like some Chaldean punk from third period. This was an unaccountable ending without a whimper or a bang. It was chock full of elemental fear, of course, which stood for something, but beyond that it was beginning to look like nothing but tedium, without pricks from horns or lakes of burning sulfur. Besides, had there been, the Escalade was equipped with state-of-the-art climate control.

Beyond that, he could think of no reason why he’d have been consigned to Hell in the first place. He’d lived a life so righteous it was very nearly unlivable. It was true that outside of his thankless job and volunteer work at the church, his thoughts were consumed with carnal matters, but these only involved his wife—the woman he’d vowed to love ‘til death them did part. The Biblical injunction against coveting was about neighbor’s wife, and he had staunchly put out of mind any temptation to peek at Lila Blessington sunbathing in her backyard. It was his own spouse he wanted, so feverishly that it had initially worried him until Father Ted assured him that marriage was about sharing all things corporal and spiritual with rightful and equitable grace: “Don’t think about it as one person possessing the body of another person; think of it as joint ownership of everything—including our mortal shells of flesh.”

Well, here he was in turgid acquiescence to Maribell’s sacred ownership and for the last seven years, she had been reluctant to take possession. How exasperating. It was, quite frankly, its own circle of Hell.

Suddenly, Prentice glanced at the Escalade’s gas gauge and found that the tank’s level had dropped precipitously. He blasted a sigh of relief, certain that in Hell, you either never ran out of gas or were perpetually running out of gas; it was never in flux. And if he was back on earth, he knew that sooner or later the storm would pass and the road would dump him out somewhere, and in lands populated by earthlings, there were gas stations to be found. More miles slipped beneath the wheels, though. The forest looked as ferocious as ever and the rain fell as wickedly and he began to suppose that instead, Hell might involve driving down a deserted country road forever, alone and lost in the dark and endlessly expecting to run out of gas.

And then the phone rang. It was Father Bartolomeo demanding to know why he was late. Prentice gulped air and refocused himself. His stomach still ground with anxiety when chastised by angry priests. “I tried to call, but my cell phone lost its signal…”

“I just contacted you on your cell phone.”

His knots made other knots; he choked back nerves and explained the situation—the detour, the tempest rains, the rutted road, the unfamiliar car and the temporary loss of a cellular device. The old cleric seemed dismissive rather than mollified. “Never mind, I will finish vespers and go to bed. Too late to drive now. We will leave in the morning instead.”

The voice disintegrated into static crackle and Prentice was afraid he’d again lost the signal, but there was a single bar, and he began to look for any break in the undergrowth where he could pull over to phone Maribell and Father Ted. They’d need an update on the revised plan, and he assumed that by now, both would be beside themselves with worry.

The downpour began to abate, the wind died back, and two hundred feet up the road a driveway shone in the headlights. He turned into it; the sign was well lit: ‘Pure Heart of Mary Catholic Church.’

He shook his head at the flukes of happenstance; he’d been on Ward Road all along. But he also frowned at the tricks that his memory was playing—not only did he remember the church as being on other side of the road, he recalled it as a simple building with quiet lines, a benign representation of moral stability and a perfect vessel for a murmur of prayer and the scents of perfume on a Sunday morning. At the head of the driveway, the Escalade’s headlights illuminated a cold and haunted-looking stone chapel pushing into wet wilderness.

Still, it had been two decades and perhaps he was conflating it with the many other small churches he’d attended over the years. No matter now; he was here. Drizzle continued to leak from the sky and he looked around to see if there was something he could use to shield his head. He snorted when he saw what was spread across the rear seat: An open map, which had been there the entire time, marked in yellow highlighter with a route that would have taken him up to Exit 202. He covered his head with it and trotted over to the church, splashing through filthy puddles despite a general affinity for hygiene, anxious to be inside where there was, presumably, a rectory telephone.

But as soon as he had pulled the heavy oak door closed behind him, he lost any sense that this was a familiar place. Filled to capacity, the Pure Heart of Mary of his youth had seated upward of two hundred parishioners, and in those days, during the popular 10:30 mass, it had usually overflowed. This Pure Heart of Mary might hold thirty, and only if they were small people.

Not only that, but the interior—lit by voluminous altar candles—was crammed with statuary. Busts jammed the ells on either side of the pews and a conspicuously large icon blocked the central nave. It was bronze, six feet tall and depicted a feminine but muscular figure reposing languidly and wearing a slight smile. A museum piece, Prentice thought, likely worth a fortune, but totally incongruous inside a rural Catholic chapel. History was his bailiwick and he quickly identified the figure as Artemis, goddess of the hunt and the wilderness.

A voice descended from the shadows; the same high nasal voice he’d just finished speaking with on the phone: “Beautiful, isn’t he? That’s Dionysus, Greek god of pleasure, festivity, madness and wild frenzy.”

Prentice squinted to make out where the voice was coming from; near the tabernacle was a corpulent old man, bald and dressed in the sacred vestments of the missa solemnis. Prentice introduced himself, and Father Bartolomeo bellowed back, “First late without a call; now early without a call.”

Prentice apologized even though problems with reception were not his fault, nor was the deluge outside, nor was the detour. Nor his misidentification of the statue in the murky candlelight.

Ember eyes glared at him from the altar. “Never mind,” said the priest. “Put out the candles and come through to the rectory—Byron has made you a bed on the couch. We have time for Chartreuse, perhaps, but if you are hungry, I am afraid that I have eaten everything in the pantry.”

Father Bartolomeo headed for an arched doorway behind the altar, then noticed Prentice trying worm around the statue of Dionysus without coming into contact with it. This amused him, so he came back. “Are you afraid to touch him?” he asked. “But why? He dares not file charges.”

Prentice drew up against a wooden pew with his groin still thrust forward, an inch from the bronze. “Stroke his cheeks, go on,” the priest ordered. “Leonardo would have been proud to do so; he is from the collection of Comtesse de Étrigny, Monaco, 1967.”

Prentice felt his breathing quicken. He was in a quandary—physically, for him, it was a salacious proposition. “Do it,” bellowed the priest.

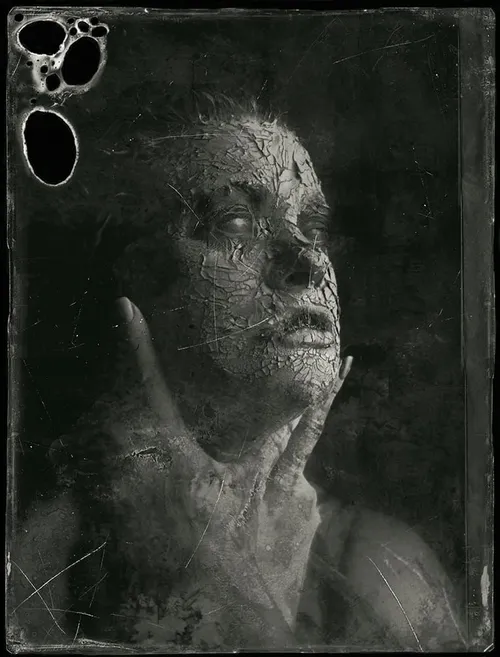

Prentice obeyed—the safest course. Gently, he touched the cold face of the statue and every inch of his flesh responded. The candles flickered fitfully.

“Stroke the lips; he will not sue you. You see how finely those features are wrought—how magically they reflect the light? That is the intrinsic strength of the medium. Now touch the ears—the armpits. Don’t you feel the preciousness, the endurance, the vitality? The tensile pith? Follow the muscles of the neck, extended in silent submission. Each sinew and cell is registered in bronze. It is sublime and impersonal—the identity does not extend below the surface.”

He stroked the icy skin and felt himself swell beneath his clothes. This was unfair—it was inadvertent. This is the way it was at school, when confronted with—well, he did not want to think what confronted him daily in third period Social Studies. Or in the teacher’s lounge on Casual Fridays. Or on weekends, at Home Depot, when the only lane available was manned by the dusky cashier with the soft Iberian lisp. He tried desperately to refocus his thoughts. He tried to think of non-erotic things; he thought of the run-over box turtle he’d seen in the school parking lot with its intestines squirting from a cloven shell. He thought of spoiled liverwurst. He thought of his grandmother.

“Move down the torso. Pectorals of passion! They defy but they do not refuse. This is the allure of bronze for devotion… For daily use.

Prentice allowed his fingers to trail to the figure’s collar bone; they stood in relief against the ruddy, metallic sheen.

“Caress him, he cannot protest. Imagine the number of hands that have palpated that chest since the 1st century when it was forged by some anonymous Roman…”

Prentice obeyed. How could he not? His flesh was provoked. The dastardly chill, the morbid deference, the non-response—it was very nearly irresistible.

“Coddle the hips, the lower back. Are not the fingers are impelled to follow the spirit into impenetrable crevices?”

The air was filled with smoldering beeswax and gloomy candlelight. Prentice let fly a sharp yip as he felt himself near climax and he gritted his teeth and let loose a deep groan of frustration.

“This is the rapture,” said the priest.

Father Bartolomeo turned and passed beneath the low, cobwebby ceiling and through the arch. Lamely, after having doused the flames, Prentice followed.

Within the rear of the church, a warm and comfortable apartment was tucked. So many valuable relics lay inside that Prentice realized the chapel merely held the overflow: Imperial statues of half-draped young men stood in heroic poses, some armless, some headless but all with sharply defined torsos. A pock-marked marble figure of Hadrian’s wife crouched in a corner by the fireplace, above which was a trompe-l’oeil pastoral scene. One wall was hung with antique marquetry, another bore shelves of Sèvres porcelain, another held a fragment of a fresco framed by a window grate that had been warped and melted by the heat of Mt. Vesuvius’s eruption.

Prentice was not aware of the provenance of these items, but when—at his tremulous request—he was ushered into the innermost sanctum to use the phone and found cabinets filled with gold armbands, Egyptian pendants, Saint-Porchaire ceramics and medieval ivories studded with garnets and emeralds, he began to wonder if the collection within Pure Heart of Mary Catholic Church was entirely legal.

Instantly, he chastised himself. A Christian must maintain clinical distance to avoid judging—this is table stakes for the Biblical enjoinder. He made his calls, leaving messages for both Maribell and Father Ted, neither of whom picked up, and when he returned to the living area, he said nothing.

Father Bartolomeo stood before a tufted loveseat beaming. It was as if he had anticipated Prentice’s thoughts. He said, “The storm has passed, yet we remain trapped by outrageous nature, within and without. Why should we not enjoy a few amenities? A nuzzle of animal affection with a piece of stone? Why should historians think that they are the only people with any say over the ancient world? Is any of this better off crumbling in a museum cellar?”

He directed Prentice to a red velvet armchair, and Prentice sat. Next to it was a pearwood table with a pewter top holding a small glass of vile-looking green liquid.

“Abide,” the fat priest ordered. “Drink.”

Prentice felt that he could not decline since the man was still wearing surplices of the liturgy, making him in persona Christi. This did not last much longer, though—Father Bartolomeo made a signal with his hand and a young sinewy man in a sleeveless t-shirt came forward and began to help him off with his vestments. Prentice was startled. He had mistaken the youth for a statue.

“This is Byron,” Father Bartolomeo said. “He is a church volunteer, like yourself. As I was saying, I am always on the hunt for the treasures you see displayed; the desire to possess such works of art is as old as the men who created them. There is no contradiction—the ancient Romans plundered Greek holy places to decorate their homes and every Pope since Peter has had his private collection. Many of these artifacts were found in Boscoreale, and since I am of Italian decent, I have more claim than most museum curators anyway—who would, at all events, happily turn a blind eye the tombaroli who excavated them.”

Prentice listened, but his eyes were drawn to Byron. He was a beautiful young man—as finely chiseled as any of the statues. His face was severe and delicate at the same time, and his yellow hair was shorn close to his scalp like a Marine’s. As one by one he removed the garments from the priest, he kept his eyes cast downward—until once, when he was out of the priest’s line of vision and his eyes opened widely and he clearly mouthed the word ‘Help.’

Prentice was now profoundly unsettled. He didn’t want to look at Byron lest the stirring begin again, but if the boy needed help, as a Christian, he was obliged to provide it. He’d begun his career as a schoolteacher primarily to rescue children who needed help. If not from upperclassmen or Monsignors, at least he could help them with history.

It was a quandary—to offset it, he began to tick off the items that the boy was removing from the body of the priest. He knew them all by heart; not only by name, but by significance. It had been a mandatory drill at St. Benilde Preparatory Academy, and in those days, when he was considering becoming a priest himself, he had learned them eagerly. The chasuble, the outermost robe, symbolized the royal robe thrown over Jesus by the Roman soldiers as they mocked Him and crowned Him with thorns. The stole represented the rope tied around Jesus as he was led through the streets of Jerusalem to His crucifixion. The maniple, as St. Alphonsus Liguori noted, was often used by priests to wipe away their tears during the celebration of the Mass.

Father Bartolomeo went on: “These days, if you find an arrowhead in your backyard it is called looting, and if you sell it, you are said to have raped a culture. Raiding tombs has long been considered a gentlemanly pursuit, and going after the connoisseur of antiquities will not stop it. Look at the engraving above the table. William Hamilton was not a ghoul, but his era’s greatest collector.”

Prentice looked; the shadowy etching showed an elegantly-dressed man with a woman in a gigantic hat peering into to a sarcophagus whose lid had just been pried open by a group of peasants.

“From that very tomb came the piece on the mantle; it depicts the death of Sarpedon. Its possessability began immediately upon its discovery, and has grown each hour since. The process is called possessification. I know of collectors who would kill to own it—that’s how strong is their lust to possess.”

As he spoke, Byron continued to undress him. Again, the boy’s blue eyes caught Prentice’s attention, pleading above a dazed, slack-mouthed gape.

The drink had gone to Prentice’s head; he cleared his throat and followed the disrobing garment by garment: The amice embodied the cloth that the Roman soldiers used to blindfold Jesus while they beat him; the long white alb signified the clothes Jesus wore while Herod reviled Him; the cincture around his fat waist symbolized the rope that tied Jesus to the column as He was scourged.

Finally, the priest stood naked except for a bizarre loin cloth, recalling—Prentice thought, despite the inherent blasphemy of such thinking—a bloated, derelict, crazy mockery of the Savior. Stripped, he seemed even more vast, like a giant, brooding baby. His flesh looked ductile, as if it had been molded in butter.

Father Bartolomeo plopped heavily onto the love seat where a sheet and blanket had been spread. He nodded, making the accumulation of fat beneath his jowls jiggle; he said, “Byron, fetch the guest another drink. Chartreuse, incidentally, is made in a monastery filled with possessions that make mine look like the wares of a carnival side-show.”

Byron disappeared into the bedroom and was gone an inordinate length of time. Silence descended. In attempt to gap it, Prentice tried to find something significant to say to the fat, naked, grinning priest with the stolen artifacts whose parish volunteer had asked for help. Instead, he said, “Is there another church around here called Pure Heart of Mary?”

Father Bartolomeo laughed out loud and his mulberry-colored eyes shone as his chin fat joggled. “Sacred Heart of Mary used to be across the street but it burned to the ground many, many years ago.”

Byron returned with the liqueur, and as he poured the drink, the thick scent of herbs rose from the glass and mingled with his own musky aromas. He dropped a note into Prentice’s lap. Prentice quickly palmed it, and after waiting what he thought would be a non-suspicious period of time, he requested the bathroom and was directed to a tiny room. He unfolded the note and read:

Dude is a sex freak. Been here a month. Soon as he goes to sleep you get me out. Be still and wait on me. This is no joke.

The bathroom was too small to pace, so he wrung his hands as he tried to figure out what he should do. He might confront Father Bartolomeo, but if the boy was lying—and boys his age were prone to do exactly that—Prentice would be forced to bear the weight of his false accusation for the whole trip back to St. Aloysius. And then, once there, what would Father Ted think? Projection from his own miserable past? On the other hand, his sworn obligation as a public school teacher was to report any suspected case of abuse. Were it true and he ignored it, his career was kaput. And this was more than a suspicion—he had the note. The note. He prayed—he prayed for more bars on his phone so he could call the Grass Lake police department and let them handle it; all he needed to do was take a photo of the note. But his prayers were not only overlooked, they were overridden—the lone bar he’d summoned had now disappeared.

In another minute, pounding came upon the door as Father Bartolomeo thundered, “It’s your business what you’re doing in there so long, but we need to make an early start. I had Byron pour you a nightcap, and now we will retire. Dominus vobiscum.”

“Et cum spiritu tuo,” Prentice responded feebly.

Ten minutes later, he crept from the bathroom and found the love seat. There was no light but that which drifted in from outside—the church sign remained lit. His best course of action, he concluded, was to see if Byron emerged to claim his escape route. If not, he’d leave in the morning as planned, and since the Escalade needed gas, he could contact the authorities from a filling station when they stopped. He was satisfied—it had the structured intricacy of a plan. It was the hard efficiency with which he’d been brought up. It was what he expected of himself.

All he had to do was stay awake, at least for a while, and he shortly realized that this would be no problem. His blankets were emanating a foul odor from where Father Bartolomeo had been sitting; the mingled stink of cologne and body filth like rancid fat. He began to gag, and the more he tried to ignore it, the worse it became. Finally, he leapt up and returned to the red-velvet armchair. It was easier to remain awake in a sitting position anyway.

The sound of lugubrious snoring began to drift from the bedroom and gradually, while Prentice sat on the red armchair, it rose to a bellow. Next to him was the nightcap. He did not normally drink beyond Sunday morning chalice wine, but the green elixir coursing through his veins had a restorative quality that he found entrancing. After all, it was made by monks in in the Alps using a secret recipe handed down through centuries. Might it not have mystical properties?

He drank it down, and shortly saw that if there was wizardry at work, it was within the statues, who seemed to mock their holy surroundings. Shadows cast by the gloomy church-sign light danced, and the faces, despite being eyeless, were blinking. Sarpedon toyed with the spear that pierced his lungs. Hadrian’s wife beckoned, but Prentice pushed Satan behind him. A screened window had been left open, and outside the frogs were an ecstatic choir singing soaring anthems that kept time with Father Bartolomeo’s snores. A mosquito lit on his cheek; he sat as still as a barnacle and allowed it to take his blood.

He took comfort in the notion that without foresight, he could have done nothing differently today, or for that matter, in his life. And foresight was reserved for prophets, which he would never claim to be. He was a simple man; he’d been born simple with the stain of Original Sin whitewashed at Baptism. We are each faced with our own share of multifaceted complications, he thought, but God has given us an immortal tool with which to solve them: Faith. Faith is a blanket, but faith is also a sharp wire that can be used to pry into the interstices and extract solutions. Thus placated, he drifted off to sleep.

He awoke to find a conspicuously handsome face two inches from his own. “Didn’t think you’d really wait up for me,” snickered Byron. “You gonna get me outta here or what?”

“If you are in trouble, I’ll take you to the police, of course. Why wouldn’t I?”

“You might be as big a sex freak as him, that’s why. How would I know? Go to your car real quiet and wait. Don’t start it or nothing—he might wake up. I’ll sneak back in the room and fetch my backpack and meet you outside.”

Prentice obeyed. The steady snoring had not been interrupted; he could still hear it as he slipped back through the chapel and wormed around maddeningly tactile Dionysus.

Outside, the storm had passed, but left stale, sluggish air in its wake. From a front row seat, the frogs were not quite so symphonic. In fact, they were

overwhelmingly loud and diabolically incessant; they sounded threatening. Prentice thought that if Hell had a soundtrack, it must include this thunder of frogs, whose trilling was like the unremitting ticking of a clock, but in Hell—where time has no meaning beyond its torment—the ticking would signify nothing, nor would one trill mean a single second closer to liberation.

He climbed into the Escalade and waited ten full minutes before Byron emerged from the church and threw a Timbuk2 backpack into the rear seat. In his rearview mirror—the one through which he might have earlier seen the map—he saw that the backpack had not been tied securely; it had been stuffed with things that were made of gold.

“You took historical artifacts from Father’s bedroom?” he cried.

“Bitch owed me. Ain’t never paid me. So now he has.”

“What if he had woken up and caught you?” Prentice said.

“He did wake up and catch me. So I clubbed him down with one of those statue heads. That’s what took so long.”

“Oh, my! You didn’t do that, did you, young man? Oh, no, don’t tell me that. I don’t want to hear that. Well, we can’t just leave now—I have to go back to see if he needs help.”

The gape through which Byron’s soft tongue had been visible now curled at the edges: “You’re a freak if you go back inside that joint, mister. You an undertaker? Only help he needs is from an undertaker. ‘Sides, second you leave, I’ll steal your goddamn car. Take the keys and I’ll hot-wire it. Try and stop me.”

Hyperventilating, snuffling and gasping hot air, Prentice sputtered, “Someone has to check see if there’s anything to be done for him. That’s not open to negotiation, son. If not me, then the paramedics must be called. We have to go to the police. If Father Bartolomeo was abusing you, it would be justifiable self-defense. He tried something queer with me, too, with a statue. Plus, I have the note you gave me. I will vouch for you; I’ll make them believe you.”

“Oh, they will believe me all right. They’ll well and truly believe me when I tell them you did it.”

Prentice tried to smile, but his eyes fluttered and it came out as a grimace. “Nonsense. They wouldn’t believe that, son. What do you take me for? All I tried to do was help you. If what you just told me is the truth, there will be forensics. It’s science.

“I’ll say you made me do it, then. Made me steal because I’m only fifteen and probably wouldn’t even go to jail. It was your idea. We killed him when he woke up and caught us.”

Prentice tried to bark, but the squeak he made did not sound convincing; every teacher has heard stories of students lobbing false accusations. They are very hard to counter. Still, he said, “That’s ridiculous, son. Backtalk and sass; think I’m not used to it? If it came to that, I’d demand a polygraph exam and pass it easily.”

“So would I,” Byron said, and leaned across the console and rubbed a sticky arm across Prentice’s chest; Prentice tried to pull it away, but then the arm trailed down to his crotch.

“There, now you got some of that fat fuck’s science on you, too,” Byron said. “Some kinda shit, huh? Explain that to the cops. Let’s go, pardner—take me to Las Vegas where I can sell this stuff. You look like you could use a road trip. I’ll blow you whenever you want, too. It’s what I do.”

No good would come from debating with him; Prentice saw that clearly. The boy was as insolent as his ninth graders, and more violent than any of them, who were all show, no go. That’s what Roger Hainline, the algebra teacher, said when they discussed the young punks in the teacher’s lounge on Casual Fridays: ‘All show, no go.’ If Byron was being truthful, and the gore stain on the front of his shirt indicated that something awful had gone on in the rectory, Prentice knew exactly what he had to do. He knew how to do it, too—he knew where he was. The village of Grass Lake was less that three miles away; Ward Road would shortly take him to the two-lane, and it was a left from there. Provided that little town hadn’t burned to the ground with the church, he remembered where the police station was—on Hoadley Street, adjacent to the post office and kitty-corner to Glenn’s Market.

No matter who Father Bartolomeo was or what he had done, or what condition he was presently in, this was a police matter and Prentice would not shirk civic duty any more than he’d have left this boy in the chapel. He would pull up to the police station and lean on the horn until an officer came out, and do it before Byron had a chance to react. It was the only sensible option available. If Byron got out and bolted, that became a police matter as well. He’d done his duty as a Samaritan and a citizen. Plus, he had the note. His story was solid; the note, a rundown of the threat to explain the smear. Perhaps Father Bartolomeo wasn’t even dead, only wounded. Maybe he would recover. He’d confirm it all, and in the meantime, let the boy think they were headed to Las Vegas.

“You sure you know the way to Vegas?” Byron asked warily.

“Indeed,” Prentice said, and, he thought, never had any way that stretched ahead of him been more well-defined.

“Then, Sin City, here we come,” Byron chortled and returned his bloody hand to Prentice’s thigh.

Prentice let it remain there. What harm could it do considering the suspicion it would allay? ‘Holding cell in Grass Lake police station here you come’, he thought to himself. He turned the SUV onto the two-lane and noted, with deep satisfaction, a sign that read ‘Grass Lake City, 2 Miles.’

As Prentice saw it, the next problem began when he saw how drastically Grass Lake had changed. The sleepy little village he remembered from his childhood had been gentrified to the point where it resembled the utopian cityscapes he’d seen in religious chapbooks depicting a glorious post-Second Coming future. It was by now the small hours of the morning, and yet, everything within the mélange of monuments and skyscrapers bristled with activity. He found himself on a ring road that engirdled the shining tableau, and was totally perplexed: This was more bizarre than finding out your wife was your cousin. Someone with immense wealth must have invested in the podunk vacation spot—that, or it was a different Grass Lake. In any case, he had no idea how to find a post office or a Glenn’s Market in this sprawling metropolis, let alone a police station.

“Dude, you outta gas,” Bryon snorted. “We going to Vegas, you better learn how to pay attention to the gauge.”

On his left, footing a towering building, was a Sinclair station. He pulled up to an expansive pump, Byron threw a wad of twenty dollar bills on the dash. “That fat fuck left wads of cash lying around the place. He owed me. Now he don’t. Use that—no sense in leaving a paper trail to Vegas.”

This presented Prentice with a maddening fix; he sat still and tried to figure out an approach. He didn’t want to leave Byron alone in the car, since he’d already threatened to steal it—hot-wire it if he took the keys. But he didn’t want to let him out of his sight either, because if he sent the boy in to pay for the gas and he took off through the shining maze instead, he’d be left with Father Bartolomeo’s blood on his clothes and a bloody smear on his thigh and no suspect to turn in. Who knew what he might be accused of? He could have written the note and invented the boy, couldn’t he? And for the same reason, he didn’t want to accompany Byron into the store—two of them, stained in gore, seen together in a gas station convenience store while a priest lay robbed and beaten just a few miles away?

“Get a move on and buy your gas, dude. Never mind what I said before. I can’t hot-wire an Escalade. It’s got all kinds of electronic anti-steal software inside it. I learned on them itty-bitty little rice-riders. We’ll get one of them soonz we get outta state. Say, what if I swear on Jesus, Mary an’ Joseph—all three of ‘em—that I won’t take your car?”

That intensified the fix and made it more maddening still. How could he refuse such a supplication? —it was almost as if the boy was pleading for salvation. Could it hurt to trust him? I mean, it was probably a sin not to. “Swear it, then,” Prentice said.

“I will,” Byron answered smugly. “But first you have to swear to them same dudes—Jesus, Mary an’ Joseph—that you won’t turn me into the police while you’re in there and will really and truly drive me to Las Vegas.”

To that, of course, he couldn’t swear, and this put the fix into the territory of full-blown insanity from which there was no way out. And yet, with faith, there is always a way out. The way out appeared suddenly at the driver’s side window, black as a charcoal briquette and grinning. A gas station attendant stood in a pristine white cap and a starched white uniform. Prentice had no idea that manned gas stations even existed anymore—this was something out of a 1950s movie or a nostalgia poster or a chapbook on Utopia.

“Fill ‘er up, gents?” asked the attendant.

Prentice nodded, and while the tank was being filled, the attendant returned to the window. “Where y’all headed this early mornin’, gents?”

Bryon spoke up quickly. “Not Las Vegas. The other way. To Boston.”

“Ah, cuz I was thinking that you both look like you could use a dry cleaner. Just up the ways, first exit on Hoadley Street, next to the post office and kitty-corner to where the police station used to be.”

“How far to the interstate?” Byron asked.

“Twenty minutes up the country two-lane,” the attendant said, pointing into the whitened night. “Las Vegas left, Boston right. Nice smooth road, too. Resurfacing finished up an hour ago.”

Prentice rolled the window up, and noticed how long it took to fill the tank in such a big car. Inordinately long, he thought. So long that the attendant went to service other cars. Through the plate glass window of the building, Prentice could see that the interior was a delirium of postmodern gas station architecture, filled with colonnades and grand staircases, multistoried, tiered and serpentine.

The time it took to fill the tank was not wasted, of course. It allowed Prentice to evaluate the situation once again. Things had changed, hadn’t they? The attendant had seen the blood and heard about their outrageous trip, the one he never intended to take but which he’d now have to explain when and if he ever found a police station. When given a chance to speak up, he had not done so. Now, it would likely pose a problem.

But, thought Prentice, even with the best intentions, our trains may be shunted onto different tracks, and this could not happen outside the ever-watchful eye of God. God’s heavenly host provides; He calms the seas and melts the ice of common fear. He provides us each with a glass case and no guarantee as to who might peer inside. Nature is harmony and counterpoint; beneath God’s fallen light, could his own life—currently a morass of misery—be possessable?

Prentice looked around; at Byron, splayed across the seat, shining in satisfaction, at the money on the dashboard, at the overstuffed backpack in the rear seat and at the glowing, freshly resurfaced road ahead.

He was not alone and he was not lost, and as for the darkness, wouldn’t the sun be shortly rising?

2.

The sun did rise shortly, but the Escalade was not discovered for three full days. Apparently, the driver had taken a wrong turn a couple of miles down a short detour and plunged off an unused dock into Grass Lake.

The coroner concluded that once submerged, the pressure difference outside and inside the car made opening the door impossible, but the car itself was so well sealed that it was likely a full hour before it completely filled with water.

Of course, he would not speculate, nor would his wife speculate, nor would his parish priest speculate, what the drowned man must have been thinking in his final hour.

This story has not been rated yet. Login to review this story.