Milton signed for the cryogenic package with his thumbprint and muttered the shortest “thank you” before dashing down the corridor as fast as his athletic legs would carry him. His frustration was only being made worse by his tardiness. He didn’t want to be late for his daily meeting with Professor Schrödinger, although he knew she wouldn’t hold it against him. She was too kind to bear a grudge, and her compassion was at odds with his anger.

Here we go again. Why do I have to run so many stupid errands for the professor? I’m supposed to be excelling at new scientific discoveries, advancing the pace of human development. Instead, I’m delivering frozen flowers to the almighty and revered Schrödinger again. It’s ridiculous. I barely have time to think about how I can use my massive intellect. Instead, it’s “collect my flowers”, “find this research paper” or “would you be a dear and make a cup of tea”. I feel like I am nothing more than a dogsbody to her. In fact, I am. I’m Schrödinger’s dog, both alive and dead inside.

As he approached her laboratory, Milton tried to calm his racing mind and catch his breath. He ran his fingers through his damp auburn hair before knocking and entering the room in one fluid movement. The heady smell of the room smothered his anxiety. Colourful dried flowers hung from the vaulted ceiling, with hundreds of mismatched bunches fighting for space. Beside a tall window, Professor Annie Schrödinger sat in the sunlight underneath a vast canopy of petals. She was browsing through her notes, making small edits, while a gentle smile breezed across her face. She looked deceptively like a favourite grandma who was perfecting a recipe for apple pies. However, Milton knew beneath this facade lay the sharpest mind on campus. When he entered, she looked up and gave him a warm welcome, oblivious to his lateness.

“Ah Milton, I see you’ve brought my tulips. Did you know I had this specific genus sent all the way from Amsterdam?”

“All the way from Europe? That sounds expensive.” Milton walked over to the floor-to-ceiling freezer and carefully stacked the package next to a dozen similar boxes. He turned and said, “Are you studying tulips today, then? It was orchids last week and lilies the week before. I wish I had just one percent of your passion for studies.”

Annie offered him a seat opposite and took off her reading glasses. “That’s where you’re wrong. You’re as passionate as I am; you just haven’t found the right project to set it on fire yet. Is that why you’re carrying a frown today?”

Milton sagged his shoulders and relaxed. “I’ll be honest with you. I’ve been feeling disillusioned recently.”

“Why is that, my dear?”

“Well, last year I was euphoric when you accepted my application to be your PhD student. I mean, who wouldn’t be on cloud nine working with the legend of the quantum field?”

Annie shifted in her seat. “I chose you purely for your scientific talent, not your flattery, but thank you all the same.”

“And that’s where my problem lies. My talent. When am I going to get the chance to put it to good use? I feel there’s a whole new sphere of science out there, waiting to be discovered. Instead, I’m spending my days in this delightfully smelly laboratory. I love helping you investigate how a human nose smells in a quantum way, and I will be forever thankful for this opportunity. It just feels so small to me. I want to go larger, massive even. I want to break through boundaries we never even knew existed.”

Annie chuckled to herself as Milton caught himself babbling. “I used to share your same enthusiasm when I was younger. But as you know, the rate of scientific advancement has been steadily declining since 1945, and that was over 200 years ago. Now it’s just the slowest trickle, a few drips every year, but it is still advancing.”

“I know in my head this is true, but my heart disagrees,” he said. “This constant battle between the two is wearing me down.”

She adjusted her cardigan and stretched her shoulders. “You need to take a step back and look at the bigger picture. Every day, we publish 40,000 new peer-reviewed papers. Each one adds one more grain of sand to an already massive beach of scientific knowledge. Either way, the beach is getting larger, grain by grain.”

Milton slapped his hands together. “That’s just it. I don’t want to be lost among millions of other scientists. I want to discover a completely new beach. Just like your great ancestry, I want my name to be remembered for something truly unique.”

She said, “Be careful what you wish for, young man. The Schrödinger family name carries a significant burden of responsibility. Enjoy your obscurity while you still have it, but I won’t stand in your way if you have bigger ambitions. Do you have a seed of an idea that’s bursting to get out?”

He cleared his throat. “Actually, I do.”

Annie tilted her head and laced her fingers together in her lap. “Okay then, tell me as succinctly as possible what has tickled your fancy.”

The word fell out of his mouth before he could stop it. “Wormholes.”

Annie feigned surprise. “Wormholes? We’ve already extensively researched this area of theoretical physics. Why would you want to study this?”

He said, “I don’t want to study the theory, I want to investigate the reality and actually build one.”

Annie laughed without malice. “My, my. What grandiose ideas you’ve been harbouring. And how would you propose doing that?”

Milton sat up. “Aha! That’s where my ingenious plan comes into effect. What would happen if we made a ring of entangled quantum particles? We could pull them apart and look through the ring and see if the wormhole exists with our own eyes.”

Annie tapped her feet lightly as she pondered over Milton’s idea. “Theoretically, that might be possible. If the ring was large enough, you might even send a light beam through it.”

“I was thinking much bigger than that,” he said.

She looked amused. “How big? Big enough to poke your finger through?”

Milton felt he was being mocked, but he knew Annie better than that. He deliberately softened his body language. “Do you think it’s possible, in principle at least?”

Now Annie became concerned. “Sometimes, there’s an impossible distance between theoretical and practical physics, and for good reason, too. However, there is only one way to find out, and that’s putting your theory to the test. Why else are we spending our days in this university?”

Milton bolted upright. “Really? You would give me some extra time to do this?”

“Of course, take the afternoons off from now on. The university has plenty of empty labs for you to use. Explore and pick the one that’s most suitable for your task. If you can’t find the equipment you need, you can always order bespoke items from the Stardance Foundation.” Annie gestured towards the expansive mosaic of dried flowers hanging above them. “I’ve heard that their purse is practically bottomless.” She gave him a wry smile.

Milton was positively bouncing. “You’re amazing. I promise to give you my full support in the mornings, without fail.”

Annie anticipated Milton’s quick exit and stopped him with her eyes. “But before you go, a few words of warning.”

Milton froze. “Okay wise guru, please enlighten me.”

Annie chuckled and then her demeanour became serious. “If my rattling memory serves me right, there was once another scientist who tried something not too dissimilar to this.”

Milton felt a sudden heavy weight on his heart. “Oh no, has someone already stolen my thunder?”

She said, “Not quite. They tried to send an audio message between a group of entangled particles. They wanted to make instant voice calls possible anywhere in the galaxy. A worthy goal, as I’m sure you’d agree.”

“Truly, but what happened? Did they succeed?” he said.

Annie shrugged. “We will never know. The professor, Alex Bell, acquired a rare form of schizophrenia. He genuinely believes he has two people occupying his mind, constantly fighting for his attention.”

“That’s awful. I feel like there’s barely enough room for me in my head, let alone someone else.”

Annie saw this look of horror playing across his face and nodded. “Don’t worry, Professor Bell has since retired to Lake Geneva for restorative care. However, if you still want to satisfy your curiosity, the university library holds a copy of his unpublished paper.”

Milton brushed away his fears. “Thanks for the heads up. I guess that’s the most logical place to start.”

Annie reached forward and placed her hand gently on his arm. “Milton, just remember that the quantum world is absurd. Particles become waves, and some things can exist in two places at the same time. It’s a weird and fascinating reality, but it’s not a place you’d want to visit.”

That afternoon, Milton sat in the quietest corner of the university library in front of the ancient homoeopathy books. He knew that only lost fresh year students ever passed through this section. Relishing this solitude, an explosion of notes surrounded him as he relentlessly studied the unpublished paper and Bell’s scientific diary.

This guy was clearly a genius of his time, much like I am, but he wasn’t without his flaws. His theory is sound and his calculations have all proven to be correct. Based on everything I’ve read, he should have been able to send an audio wave through his quantum wormhole. It looks like he reached this point just before he lost his mind. Imagine if it was bigger and you could send supplies through it, like a thin jet of oxygen, to distant spacecraft. With a bigger hole, you could send a stream of water to distant colonies. Or with a bigger portal, you could even step through it. The possibilities are endless. The implications are massive. I need to think and build bigger.

The next afternoon, Milton explored the university and stumbled across a pair of rooms that offered a unique opportunity for him. They were medium-sized and identical in shape, with two-metre thick steel alloy walls between them. Both were well lit, clean, and a long walk away from the access lift and prying eyes. They hid perfectly in the basement. He keyed his student reference number into the screen outside both labs, allocated Annie as his designated professor, and commandeered the rooms. Lights above both laboratory doors changed from green to red.

Over the next six months, the Stardance Foundation regularly delivered duplicate pieces of equipment so that he could build two identical machines from the ground up, one in each room. On completion, he decided they needed names. After a brief consideration, he called the one on the left “Jules” and the one on the right “Verne”. The final construction part of the project came to an end on a Friday afternoon in August.

Milton checked his watch and saw that it was getting late and an all-too-familiar hunger was making itself known. He made a promise to himself to recuperate over the weekend and test the machines on Monday afternoon. That night he couldn’t sleep as his two magnificent beasts that slumbered in the bowels of the university skyscraper haunted him. So, like an excited child on Christmas morning, he finally crumbled at 10 a.m. on Saturday morning and made his way back to the lab. And that is why, at 11 a.m. on Saturday 7th April 2147, Milton stepped into the world’s first, and most dangerous, quantum travel machine.

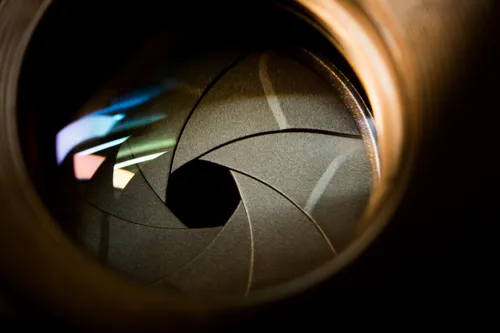

Inside Jules’s booth, there was just enough room for Milton to swing a proverbial cat. He took advantage of the basic but comfortable seat that faced the aperture. As the door sealed shut, he took a moment to run his fingers down the brushed titanium walls. Immediately, a silent breeze from the air conditioning unit grazed the back of his neck. He was hypnotised by the metre-wide aperture in front of him. It looked not dissimilar to a camera shutter mechanism, with the polished copper blades obscuring his forward view. As tension rose in his chest, he realised there was no going back from this point. If the device worked, he could publish his scientific paper and take that ultimate step forwards where Professor Bell had failed. He took a final deep breath and keyed in the open command.

A pinprick of light appeared in the aperture, which rapidly enlarged like a star going supernova. Before he had the chance to exhale, the blades sprang back on their gears and the hole opened in its entirety. A sudden wave of energy hit his mind and touched every nerve ending in his body. A flash of painful, blinding light was so bright he thought it had actually incinerated him. But when he realised he still had eyes and could open them, what he saw confused him.

Initially, he thought it was a mirror, as he was looking at exactly the same room and a reflection of himself. In frustration and confusion, he reached up and scratched the stubble on his chin. The reflection copied the same action, but the movement was out of sync. An icy wave of sweat prickled down his back and his jaw opened involuntarily. He tipped his head to the side like a curious dog, and the reflection leant back in surprise. Both Miltons scrambled out of their seats and pressed themselves against the back of the booth walls.

The Milton in Jules’s booth stuttered. “Who are you?”

“I was going to ask the same question. Are you me too?” said the Verne version of Milton.

Jules said, “I can’t believe it. If I’m looking into your booth, then the experiment must have been a success. There is no wall blocking my view.”

Verne said, “You have a strange definition of success. I can see a mirror image of myself that is acting independently, and it’s quite unnerving.”

Jules paused. “Wait, you’re right. Why are there two of us?”

Verne rubbed his cheeks. “It must be to do with the quantum entanglement. There must be an equal probability of us being in either booth.”

Jules pondered over this logic for a moment. “If that’s true, then it doesn’t bode well. For a start, how do we stop being in two places at once?”

Verne stared back and said, “We don’t need to, as there’s only one of us, me, and you are my reflection.”

“No, no. I’m Milton,” said Jules.

Verne said, “But if I’m in Verne’s booth, then I must be the real Milton, because the experiment worked.”

Jules said, “No, it didn’t work because I’m still in Jules’s booth. However, this is a minor point, probably a glitch in my programming. I’m sure I can iron out any bugs and erase you later.”

Verne pressed himself harder against the wall. “I definitely don’t like the thought of being erased. Why don’t you erase yourself?”

“Don’t be ridiculous, I’m the real Milton.”

Verne said, “I beg to differ, and this petty argument is getting us nowhere. I didn’t realise just how stubborn you can be until I met you. Anyway, it’s been a pleasure talking, but this flawed experiment is over. I’m getting out.”

Verne peeled himself from the back wall and faced the exit. With shaking fingers, he reached forward to pull the handle and open the door. His fingers could sense pressure from where the handle appeared to be, but he couldn’t apply any force. His touch felt like mist trying to topple a mountain.

Jules watched him strangely. “Well, go on then, get out.”

With a slight tremble in his voice, Verne said, “I can’t.”

Jules snorted. “Don’t be ridiculous. Let me try.” Jules tried to open the door in his booth, this time with both hands, and encountered the same problem. “I… I can sense the handle, but I can’t touch it.”

Verne said, “Maybe that’s because we are a probability wave, and not a solid particle.”

“If we are the peaks and troughs of the same quantum wave, we can’t exist completely in either booth,” Jules said. “We are in two places at the same time. Which also means we are stuck.”

Verne felt his temper rising. “This is all your fault. You’re always rushing ahead without due diligence. Why didn’t you build a kill switch inside the machine? Or a timer that would close the aperture after 5 minutes?”

Jules said, “Don’t blame me, you’re equally to blame.”

Verne sneered. “No, you’re the arrogant one. You’ve always been too overconfident.”

Jules threw a challenging look of disdain. “Without that confidence, this machine wouldn’t even exist.”

Verne tried to bang the wall with his fist and failed. “And now look at us? Trapped in your contraption with no way out?”

Jules slumped down onto his stool. “We’ll get nowhere if we argue with each other, both figuratively and literally.”

Verne said, “Then we have been idiots. We should have kept the experiment on a small scale.”

Jules nodded in agreement. “In retrospect, I think so, too. Annie warned us that quantum physics becomes ridiculous on larger scales.”

“Our situation is truly that.”

Uncertainty crept into Jules’s voice. “At least we will be famous?”

Verne said, “I have a horrible feeling that this fame will be posthumous. I’m way too young to die, but that is exactly what will happen if we can’t get out of this wretched machine.”

Jules sank further into his seat. “What a dreadful thought. I don’t want to die in here either. But how can we die if neither of us is 100% real?”

Verne flopped on his stool with all the grace of a beanbag. “Maybe we’re already dead and this happens afterwards. An eternity of probabilities, some higher, some lower, but never anything concrete.”

Jules said. “Hang on a minute. Do you think this happened to Professor Bell? As far as I can tell from his paper, he built his quantum telephone and then went mad.”

“So what?”

Jules continued. “What if, in order to test his machine, the first call he made was to himself? It would be simple enough to hear the audio of one device and speak into the other. Maybe he had a conversation with himself, just like we are. And promptly went insane. And we will do the same, lost in our minds until the end of time.”

“At least we won’t be alone for all eternity.” Jules gave a short laugh. “And I have known you my whole life, so we’ve got that going for us.”

Verne broke into a cautious smile. “That’s true. We have our flaws, but we’re not all bad. A little arrogant, maybe, but not insufferable.”

“No genius is without their flaws,” Jules said. “We are like Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.”

“Bonnie and Clyde.”

Jules said, “Thelma and Louise.”

“The yin and the yang.”

Jules smiled. “But I’m still at the peak of the wave. You are in the trough. Don’t you see the irony? Instead of discovering a new beach of knowledge with billions of grains of sand, we are the wave forever lapping at the shore. Oh, how our grand plans have collapsed around us.”

Like a jack-in-the-box, Verne sprang out of his seat. “Wait a minute, I think you’re onto something. If we’re stuck as a probability wave, it means there’s still the possibility of being a particle, of becoming whole again.”

Verne’s enthusiasm rubbed off on Jules. “Go on, I’m listening.”

Verne said, “All we need to do is collapse the wave.”

“And how do we do that?”

“It’s as simple as identifying our exact position,” Verne said. “We need to be observed.”

Jules’s eyes opened wider. “That would do it. The current Milton is in both booths but as soon as someone opens the door, the probability wave collapses and we, or I, will exist in only one booth.”

Verne said, “Bingo!”

Jules jiggled his legs with his toes. “There’s just one problem.”

“And what’s that?”

Jules said, “We have no way of contacting the outside world.”

Verne ran his fingers through his imagined sweaty hair. “When we commandeered these rooms, we had to allocate a professor for authorisation. The only person who could know we are down here is Professor Schrödinger. When we don’t turn up to her laboratory on Monday morning, she may get concerned and try to locate us via our access tag.”

Jules said, “Yes, you’re right. There is a slither of hope after all. Good old Annie to the rescue.”

Now it was Verne’s turn to laugh. “But in the meantime, the two of us are both alive and dead until she finds us.”

Jules crumpled a little. “And so we wait.”

Verne’s tone was more upbeat. “At least we have a solution of sorts. And with all this time on our hands, I suggest we tackle the problem of your arrogance. It needs to be taken down a notch or two.”

“My arrogance?” Jules said. “It’s your arrogance too!”

Verne gave him a stern look.

Jules put his hands up. “Okay, okay. It’s always good to talk things through. It’s not like I’ve got any plans for the foreseeable future.”

Outside the booths, time passed at a reassuringly predictable rate. By 11.30 a.m. on Monday morning, Annie’s curiosity and frustration at Milton’s absence led her all the way down to the 30th sub-basement. Milton obviously couldn’t hear her come in and missed the polite tapping on the door. It was only when the door handle moved that the exhausted Miltons looked at each other and simultaneously said, “Annie!”

As the seal around Verne’s door broke, a look of horror washed across Jules’s face. Milton sensed a distant, heart wrenching scream that burnt down his spine as Jules blinked out of existence. He experienced the same blinding flash of pain as his probability wave collapsed into 100% certainty. The door opened fully and Annie poked her wise, wrinkled face into the booth, bringing with it a familiar aroma. “Oh Milton, there are you.”

He composed himself as fast as he could. “Professor, I’ve been expecting you. I think the door got jammed, so I appreciate your timely rescue.”

Annie looked worried. “When you didn’t come to my lab this morning, you had me all in a spin like a dizzy bee. Oh my, how long have you been trapped in here?”

Milton shuddered. “Not long in the greater scheme of life.” He stepped out of the booth and stretched his arms high above his head. As his hands returned down, he carefully plucked a dried flower petal from Annie’s thick, silver hair. “This rose petal is yours, I believe.”

Annie twisted the petal in her hands and laughed. “That’s a carnation petal. Oh, I wish you’d focus more sometimes.”

Milton opened his arm to guide Annie out of the lab. “Trust me. I’m more focused than I’ve ever been. Come on, let’s get back to your lab and I’ll make us both a cup of tea.” He flicked off the lights and walked down the long corridor to the turbo lift as Annie chatted away lightly.

Milton felt emotionally sick and tried not to review the last 48 claustrophobic hours.

I could swear I heard a scream when Jules disappeared. But that can’t be true, as he was only a probability. Which means he may still exist. I wonder if he is still alive somewhere?

Yes, I am. I’m right here. We both are.

This story has not been rated yet. Login to review this story.