In primal times somewhere there spread a vague expanse of land without any boundaries; an area of foggy swamp and straths of forest inhabited by savage, warlike, uncivilized tribes. During the gore-month, the month when cattle were slaughtered, one of this race, a stubborn hunter in his prime, stood before a darkling pond and waited. Neither his kin nor his neighbors had much cause to come so far past their settlements; the pond sat within a gloomy pine grove at the heart of a haunt beyond the farthest homesteads, even beyond the grave mounds and the sacrificing-places, nearly beyond the compass of the snake and the eagle. He'd discovered it by accident some weeks prior, tracking a reindeer which had fled down from the rime-stones. Nameless muddy streams disgorged their quickest venoms here, the rushes were alive with lapwings; yet here he waited. His mind was embroiled in contradictions. He tasted the foul mists which rose and sighed between the firs. Dreadful, foolish imperatives clung to his loins like ague.

Several times now, he'd seen a human female here, pacing to and fro among the trees, silent, naked, dark and lean as willow strands, and she'd so seized his awe, for reasons he could not name, that he'd returned three times, at closer intervals, to spy upon her, intently and passionately, without daring to approach or to make himself known. His shyness was unaccountable, especially to himself. That he, who paid such great attention to toil and hardiness, who refused to change his countenance because of wounds, who might live a week or more without food, would be so disturbed and intimidated by a woman. A girl, in fact; she couldn't have been beyond fifteen years.

While he waited, he clutched a satchel; within it, there was a stag's liver and a choice joint-bone. The bundle itself was a hide stripped from the same creature, which made a garment when unfurled.

He gazed around for many minutes and nearly missed her. She appeared as a wraithlike form moving in the windless air, rising against the exhalations of decay in the cold and silent pine forest. There was a deeper smell accompanying her; he judged it to be carnal, but it might as well have been brine-air from the far-off shore. Her hair was dark and flowing; she wore it loosely as was the custom of maidens. It partially obscured her. Scant modesty; as before, she was naked. He watched her and marveled; her hands were tapered and painfully beautiful. Her skin had a russet sheen; her hair was so dark it was almost blue. Such colors were unknown in those frozen districts, even if you traced it back throughout numberless winters, back to when the world was shaped. By her very demeanor, in fact, she appeared to be possessed of great, potent, otherworldly emotions.

But, he'd heard that there were many kinds of people alive, many tongues and many colors, and he never assumed that she was of any sort but a mortal child under some enchantment of her mind. She was of supernatural beauty, beyond question, but he was an overbearing and headstrong man and his practicality would not assimilate the idea that she could be purely supernatural. To him, long poems of records were too enigmatic to be followed much less understood. The dreamworld and the real world did not intermingle so far as he'd determined. No matter the local superstitions, the dryad-tales of siren-voices, the forest nymphs, the faeries; for him, nothing could exist before, and nothing beyond; they were alone, and he was sure of it. It was a frontier life, made dire by struggles, bold and innumerable dangers, with nothing but a gaping void on either side.

Yet still, he stood in dreadful anticipation. It was self-disgust that finally bolstered him. He strode forward to the shores of the pool, a shivering throughout his body that was akin to sickness. "What's your name?" he shouted out at last.

"I have none". Her voice came back, softly, without a tremor of fear or surprise.

"Aye? How do you come to have no name?"

"I have no need of one."

"At your birthing, didn't they fasten you a name?" It occurred to him then that by her coloration, she might have been considered an abomination by her parents, a changeling, some faerie trick, and placed out on the cairns to die. She'd survived somehow...

"Well, what of it?" he cried. "I was also left exposed on the rocks. And also lived." So he had; having been judged unlucky by the temple-priest because of the way his stones had fallen. But, hearing his pitiful wails in the callous season, his father had relented and rushed out to sprinkle on water; after that, his countrymen had to accept him or stand accused of murder. That's why he'd grown into manhood so utterly opposed to the concept of predestination, the traditions of hereditary luck and good fortune. "So we are kindred, my child."

"So, we are," she said.

His heart was hammering against his chest, but he pushed forward boldly. His father had told him that true courage is how a man behaves when he feels no courage. "Well, I must call you something. Little Dark Thing From the Water, then. How's that? And with the name, one must usually offer the fastening." He thrust forward the deer's liver and the skin, which were traditional gore-month gifts.

"I have no need of those," she said.

"Then I will go and make warfare and get you some victories." Traces of sarcasm licked the tone.

"I have no need of them," she said.

"So, you need no name, no food, no clothing, and you are not greedy for any properties. How does that happen to be?"

"I am a dream," she said, simply.

Lust now overruled his trepidations, and he considered the ways which he might seize what he required if she would not trade it. "Aye?" he shouted back, pushing to the edge of the water. Entering. "Yet, I've known dreams that could eat all sorts of food. Dreams that dressed in every manner of frock..."

"But need not," she said.

"And therefore, am I asleep?"

"Thou art not."

"Awake, then?"

"Thou art quite awake."

"Well, then, how do I happen to dream you if I'm awake? Understand what's wrong in that? I can see you plainly. God, I can even smell you."

"And dost thou believest in the God of whom thou didst tell me now?"

"By no means," he confessed.

"And the white Christ in Heaven?"

"I do not."

"Then, since They stand no less plainly before you; why believe in me?”

He snorted. He had a coarse woolen cloak and breeches fastened to his legs, which he now stripped away in ferocious, angry strokes.

"Well, you are real enough for me, Dark Thing From the Water. Your presence has driven me to madness. I am now beyond reason. You may do your fast and have your cold vigil here in the woods; you can speak your allegories, but you can't continue to taunt me with your dream-sex. Your musk alone... hah, as you can see, I have brought a blanket and I'm prepared to fuck you, here in the mud, and no matter the cost. I think it proper at least to offer you something in return. I am not possessed of family estates. What will you have from me? Say it quickly..."

"Proof that thou art prepared to fuck me, no matter the cost. Thou keepest a wife, do thee not? Can I not see her through the afterbirth she stretches across the window hole? The young boy sleeps; now she sits by the peat-fire, on a bench clothed with a layer of straw; she's weary and combs out yellow hair..."

"What of her?" he asked, moving forward, entering the morass to his bare calves.

"I want whatever she loves best."

"She has little enough by way of valuable things. We have only a small hovel, nothing but a plate, knife, threshold; even her bed-hanging is woven mistletoe from the garden. What could you want from her?"

"Whatever she loves best."

"She has nothing, which you would know if you saw what you pretended to see. How am I to choose from nothing for a gift to give?"

"Thou needst not choose. Thou needst not give. But once done, thou may not take it back; what thou givest becomes mine forever and may not be had again. Except as I choose to give it back."

Now, he scoffed. Only bards and idiots spoke in riddles. He went past his knees in the mire. He was swollen with hunger for her, past reasoning. What followed, if not offered, must prove to her to be compulsory. "You would try to wrest control from me? You? A naked child alone in the ugliness and gloom?"

"Where thou seest gloom, perhaps to me, it is sublime. But, control? Control is thine, as always. I'll stay in solitude or lie in mud with thee; to me, it is the same."

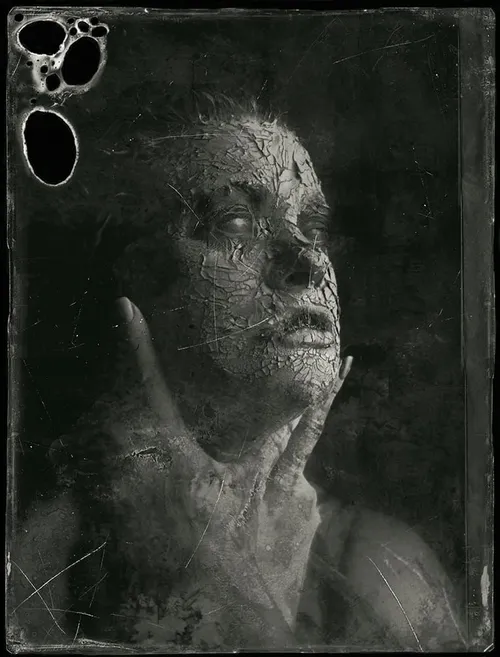

Black water reached his waist, and he was sinking deeper. He looked down, saw amid the lapping fen the reflection of a large and fierce-looking predator. Himself. And he knew a little shame. When he looked back, she was gone. Somehow she'd slipped away among the firs, evanescent as dews that drop in the dales, and even with a hunter's eye, he couldn't find her again.

He arrived late to the hovel, with the red moon cowering behind clouds. He peered through the window membrane, and it was the very image that the dark thing had divined; Nikola sat with her bone comb, carefully fixing her tresses, while their little son slept before the hearth on a woolen pillow filled with down.. He was suddenly amazed; not at the accuracy of the prediction, but at the simplicity of the solution. For all her scant possession, Nikola had one thing she appeared to love with inordinate pride; she grew the most beautiful locks he'd ever seen; they were the pride of her sisters, the envy of friends, and the dark-haired changeling must covet such angelic hair with demonic passion to demand it in exchange for her maidenhead. Yet if that was the cost, it was little enough...

Once within, he wouldn't eat nor speak, and Nikola tried patiently to prod responses from him, to learn the source of his unexpected spleen. He'd have nothing of it, naturally, though as he accepted her comfort, he recognized that the air within the room was lighted from her graciousness, and he questioned the depth of his own insanity to consider betraying her. Soon, he lay beside her and slept.

That night his brood of dreams contained every manner of confusion and anxiety, though no swamp girl appeared within them; rather, faceless rogues broke blood ties, brothers slew brothers, mothers dashed their offspring against roof beams and spilled out their brains; there was whoredom and famine and it went hard everywhere in the world; the she-bear was screaming in death-throes, the eagle was devouring the snake, the wolf was gagging on its own saliva; serpents lashed the waves, vapors raged, suns blackened. He awoke in a sodden fit, unable to catch his breath, and Nikola held him and soothed him, and finally, took him with gentle, accommodating indifference.

The act humbled him, but did not calm him much. He sensed a remote kind of superiority about her. As soon as she was asleep again, he rose, moved to the bench and began to examine her bone comb with steady, frantic concentration. He found a strand of yellow, then a second, and began a wild search by the hearth stone; he kicked up the peat, found a third stray hair, but that was all. Her luxuriant tresses were not prone to exile. Three hairs in his palm looked like a paltry gift. It hardly seemed to constitute recompense worthy of the dark compulsions goading him. He began to scour the dirt and cracks by the tinderbox, then, her folded frock by the firelight. Increasingly desperate, he found more hairs among a heap of shavings from some carpentry he'd been about, but they were shorter and very fine, and likely belonged to his son. They'd never fool the dark thing; he was certain of it.

He paced and clutched at himself and plotted. It became clear. He knew he might blame any sudden outburst on his nightmares. In a moment, he buried his face in Nikola's hair, and heard her breathe in rhythmic shudders. He told himself that her hair was too much a source of girlish arrogance in her to require so many minutes at her toilet when she might better have been at mothers' work; that she must renounce her Christian faith and marriage role, or else, call herself a hypocrite. He seized a handful, and carefully wound it around his hand, thumb upon the palm, closing his fingers on it. She slept on in sweet abandon; she murmured softly. With calculated savagery, he tore the handful from her head. She screamed, but it went as he had conspired that it should go; she held her scalp and wept, but spoke to him as if he was the one abused. Such abuse!

And his mind told him that nothing but evil would come of it.

Yet, he was back to the grove before the morning fogs had cleared. Snuffling and sorely aroused. In time, the dark thing appeared there; she took the gift from him and flung it instantly away into the swamp, where it floated across foul black water like a funeral boat and slowly sank.

"I've desecrated my bed, my contract, my family to fetch you this gift, and now, you only cast it off?"

"It is mine to do with as I please," she replied nonchalantly, but suffered him to approach through the morass without foundering, and he forgot everything else as pressed her body hard into muck, chewed away at her cold skin, smelled the distant sea within her fierce mouth, held her down so that the blue algae blooms lapped over her breasts, and accomplished his act with the passionate outrage of a temple priest performing Blood Eagle… the slitting of the victim's spine, drawing the lungs out through the hole… whereupon, he wandered off to the cairn stones and lay as one stricken among the clay pots and unburnt skeletons.

Only one question haunted him. What sort of meal? Where one feasts, then grows hungrier for the food?

He returned to the swamp the following day. He'd not slept the night before, but only fretted and groaned and relived the ghastly glory of that morning tryst. He'd been sated, so completely yet so briefly, that his young life seemed to be altered irrevocably in an instant. Already, he was past bargaining. He'd vowed to have her again, there in the filth, whatever the cost. And the cost was the same. "I have given you her the very hair torn out of her skull," he cried in a sweat of panic and desire. "What more could you want?"

"I want whatever she loves best."

He paced the swamp banks, but could not seem to enter far without sinking. "She has nothing," he howled.

"So thee hast told me. Not once, but twice. Think on."

She had, however, a little flat finger-ring which he had forged himself to consecrate the marriage. It was of silver and alloyed gold, formed like a spiral, with a flat carnelian in the middle. He'd not considered it, despite the clarity of this solution, because it represented vows more sacred than any fistful of hair.

With the sudden revelation, he screamed: "It's madness! She never takes it from her finger. I'll give you her bodice. Or her comb; she'll have less need for it now. But I'll never get you the ring."

"What ring? That hallowed thing which girds the finger of thy companion? Thou needst not get it. Thou needst never give me anything; it's all the same to me. But once done, what thou givest becomes mine forever and may never be had back again, except as I choose to give it back."

"You dare speak to me of repetition? You've grown intolerable with your own," he shouted. "I want you, now."

He was to his chest in the stinking pond, thrashing madly, feet wedging into thick black filth, before he understood, absolutely, how it would have to be.

He returned to the hovel, his fever high, nerves quivering like an insect wing; but his process had gradually been formulated along the way. Without a word, he fetched a hazel peg and pretended to have an urgent need to drive it into the midden as a gatepost. And then, when he could not appear to aim it right, he called for Nikola, and begged for her help. She need merely steady it for him; the ground was hard. He bade her hold the thick branch with both her hands, hold it erectly and firmly above the hole he'd begun; he warned her with perverse solicitude to hold it with extra caution, and when he brought the mallet down, with tremendous force, he purposely missed, and struck her ring-hand while his son stood by with wide, bold eyes, and watched.

He needed reckoning to justify himself; the deed had been more insane than those of the district's worst beserker-men, who tore out tree stumps when they had a fit rather than hurt their friends. And so he reckoned that whatever vows he feared to violate had been already broken, and by that, he found his conscience somewhat palliated. And while in the midst of attending Nikola's horrible wound with kind apologies and a poultice of moss and silt, he twisted off her ring and slipped it into the folds of his garment. And his mind told him that nothing but evil would come of it.

Nikola was scarcely laid upon the bed furs before he found some reason to be gone; and then, rushing back toward the gloom, wooed the insouciant child with the ring and watched her cast it into the heart of the swamp with no more feeling than had it been a pebble; but she silenced his protests by clutching his heaving back and giving over what he craved.

That night, though Nikola attended her work in a welter of pain, he sat at the greasy table and grumbled over every detail: the butter was thick with cow hair, the milk was not hot enough, the turf soot choked his throat, the son had snot on his face. She wanted consolation for her injury, and he had none to give her; it was as if his heart had been struck with a flint dipped in hemlock. It was she who offered understanding for his wicked temper, and him that took it, though his regard was not nearby, absorbing her grace, but off in shame beneath the vile, corrupted waters.

And so, he tried to push it from his mind, to lose himself within the tasks that must accompany his survival in that wild existence. He fetched his pair of bows, one of yew and one of elm, his arrow-shafts, and paid great attention to his hunting. Hourly, he tried to quench the lust-fires by bathing in the coldest waters. He made it three long days; days so filled with torment and joyless confusion that he scarcely knew what he was about. He slept in dirt, ignored the rain, fed on nothing; he tracked among the rime-stones and beyond, and finally, he found a fat hart nibbling ash buds, and again was led into the lowlands and the pines, as he realized that in time, he would be.

When she came, he was no longer bold and manly, but craven and pathetic. A stout breeze stirred the lifeless air, arousing scents of sober truth, both rot and reproduction. "She has nothing," he whined. "Even the hovel is not mine to give; it's jarl-owned. What more can I take from her? What more can you want?"

"I want whatever she loves best."

"She is a Christian girl, she holds firmly to that belief; she doesn't place material importance on those things which you might covet. But damn me, child, I'd give anything for a taste of you." He couldn't help but touch his tongue to his lips; even a thought of the brown skin made him giddy. "But if that's your cost, I'm ruined; I have nothing left to give; she loves nothing now; she holds nothing dear except her son. Me, I am beyond control…"

So saying he charged her, hoping to outswim her or run her down, and he collided fully with a shrub willow that stood where she had stood.

He stormed away. And stormed for two more days. And in the storming, conceived thoughts that were so abhorrent, even to himself, that he questioned his ability to take in another breath of life. Back at the homestead, he discovered Nikola the worse for her hand-wound; she had by then grown so ill that she could not rouse herself from the bed. She lay in a swoon and begged him to take their son to those among her clan who could care for him; the boy had scarcely been nourished nor comforted in all those hours. And so the hunter found himself leading his young son across the fields. In one hand, the boy held his father's, in the other, he clutched at the rag toy which he needed to cheer himself. As they walked, the father saw that he held within his very grasp the key to his deliverance; though he might rather die for the wish that he might have seen it differently.

But, there was no space for that; and no real time, and shortly, even the boy understood that they had changed their course, and were not headed toward the farms of relatives, but across the open heath, down into cold and execrable forests, where a lean dark maiden stood like a solemn idol, as if in wait.

The young boy whimpered and squeezed his rag toy. "Go to the girl," his father ordered. 'She will nurse you while your mother recovers her hurt. Go on, God damn it; this one cannot harm you, she's not real enough to fear by her own admission."

The boy cried and refused to release his hand. "Go to her," he railed in a sudden passion. "Have I not said twice to go to her? Boy," he raged, "you would not dare to cross me! Go to her!"

As the dark thing stood with arms outstretched, her face took on such a low sheen of radiance that the child stood trembling and vacillating until the father fairly shoved him forward into the swamp. The dark girl seized him up, and flung him out into the wastes, where he screamed and struggled and sank. As an instinct, his father sought to save him, but it was no good; he couldn't gain footing in the shifting mud, nor swim at all, and he watched helplessly as the boy was swallowed by the inks of eternity. And yet, when it was over, he did not fret for long; he lay down atop his black prize with steady jabs of rapture, not horror. He was so far removed from what had happened that, had he not found the little corpse afterward, eddying gently by the banks of the pond, he might not even have recalled it.

He saw upon the boy marks of death, and none of life. He wept, like a father would, and he carried him far away to the point where the rivers fell from the mountains, made him a bath, as was the custom, washed his hands and head, combed and dried him, took him to the sand plain below the skeleton graves, and there, with the rag toy laid upon his breast, bidding him sleep happily, he mounded him.

At home, he stood stupidly before the bed. "I've lost the boy," he said. "He's drowned in the pond."

There was shortly a gathering of drawn faces, much regard for the forlorn couple, many words which had a ring of truth, though as to the actual truth, he had to hold it inside. But he held Nikola as well, who herself now seemed to be upon the shores of death; they grappled at each other in their sadness, touching the deepest fonts that sprung from within themselves; as they had loved and grown together, now they grieved together. They could do nothing else. And sincerely, too; though in the end, it's fair to say, he was less sincere than she.

He was not beside her for a single night before he wanted more. He went outdoors, and a great black sky wheeled overhead.

He went again to the swamp. New and strange imprecations came to him. He tore his own hair out. "I need you," he shouted to the savage vacancies.

The place was changed. Where the air had been thin and lifeless, a tempest wind kicked up, spewing mists of damp decay throughout the hollow. Still, the girl's voice was not engulfed by it, but was virile and loud, as if it had begun within his own ears. "No," she said. "In truth, thou needest me not."

"I do!" he insisted as the wind blew spit back across his face. " I do! More than food, more than the blood that moves in my arm..."

"In truth, thou hast need of neither food nor blood."

"Wretched whore, you make light of truth now? You've drowned my son. His mother herself will succumb to the wounds that were administered on your account. I will give whatever you ask. What else is there?"

"There is as always. Whatever she loves best."

"Damn those words. Then I must present you with all the world for a single sniff of your skin; she loves the world, by God, she has no space for any emotion less. She's proved it now. Beyond the fiercest doubt. Even though I have torn hair from her scalp, crushed bones in her hand, sold our wedding compact, murdered her son, yet she loves me! Even me..."

And the way was suddenly clear, though he believed that nothing good could come of it. He stood fixed in wonder. "You ask me to give myself?"

"There's nothing asked. Only what is freely given. Though once done, what is given remains mine forever, except as I might choose to give it back."

He strode forward quickly, across the wind-ripped surface of the pond, so resolutely, so readily, that the dark nymph was impelled to hold her hands aloft. "Thou wouldst accept thy own annihilation for the sake of me? Where is the sense in that?"

"Who cares for sense? I have long since lost what little I had."

"What rationale draws you onward, then?"

"None, black bitch, but what does it matter, since I am prepared to accept your bargain?"

She ran her long fingers over her lean and feral figure, now glistening wet with rain. To him, this action made her the more maddeningly desirable. She said: "What good is this if thou losest thyself?"

"What self?" he cried in final contempt.

She pointed downward. He was amazed to find himself suspended at a hand's width above the pond. He looked and saw the reflection of some withered beast writhing in reptilian torpor, sloughing putrid flesh in strips as if it had stepped grinning from the grave. It seemed to shift in concert with himself, moving whenever he moved.

"What is that cursed thing?" he screamed. "Who is that creature?"

"Thyself," she answered

In tears, now, he bellowed with all the strength of which his voice was capable: "How can it be? I've said! I do not believe in sorcery or foretelling".

"Nor should thee. There is no such thing."

"Then how does that creature happen to be called myself? You are the dream, by your very words... how does my face become this… thing?"

"Because," she said with easy grace, "Thou art a dream as well."

And she permitted him to approach her, and afterwards, urged him downward; sent him sinking deeply and completely beneath the polluted ripples.

* * *

Vague straths, foggy dreamscapes, districts without boundaries. An eagle was eating a snake. He opened his eyes. Gradual focus. Far off, slack, scruffy hills, thorny scrub, anemic cacti, pathways that didn't appear to lead anywhere. Nearer, dusty backstreets, which in the sullen afternoon were heavy from the narcotic calm of nonchalance. A lot of fucking head pain. The occasional yip from a viejo drinking pulque and playing vienti una. The sun was sharp, unrelieved. He was sick to his stomach. A mongrel made a snuffling sound in an alley. It ought to reassemble in a minute. A minute passed; it didn't reassemble. He faded away again.

A man was passing. Mayorico. He recognized the injured man as one of the barrio's floating population, a blonde gringo junkie who lived on the rake-off from various small-time narcotraficante connections, half-kilo sized deals. An addict who'd thought that existence would be cheap and complaisant down here and found another version of hell, albeit, for awhile, a speechless one. Drugs were the emotional and financial heartbeat of the seedy little barrio, and no day passed without someone turning up in the plaza, robbed, clubbed, or even shot. The gringo was harmless enough; nothing but an irritating pinkie stuck in the major pie.

The vultures had pretty well picked him clean. Going through his pockets, Mayorico found a small spiraling piece of gold that somehow, they'd missed. He'd have palmed it, but the gringo began to come around. Mayorico left the ring where it was.

"Que pasó?" The gringo was making strange sounds.

"Life in the shit yard," said Mayorico, showing a troupe of bad teeth.

"What...?" A weak comeback. The gringo was looking at his hands, which were filthy, caked with dried mud and vomit.

On one side of the plaza, an old priest was sweeping volcanic ash from the chapel step. On the other side, a mueble shop was filled with hideous furniture. There was a parched fountain, the smell of cement and piss and bugambillia, narrow, balconied streets with pink, terra-cotta facades that looked like pastry icing. There were bullet holes in the chapel.

"...you don't look so good," Mayorico was saying "...but me, I'm a cynical SOB to begin with."

"Could use a hit," the gringo groaned.

"Bet you could."

The blonde man had a peculiar thought. He had no idea who he was.

Mayorico got him to his feet, slapped at the crust of dirt that stuck to his dungarees, helped him to walk. As they passed the wooden door of the church, Mayorico made the sign of the cross and dug in his pockets for a handful of pesos to give to the old priest, who was wearing a shawl despite the heat. Mayorico looked at the gringo expectantly. "God preserved you this time. Surely you can see that?"

"No, I can't. I don't think in those terms. Sorry."

They took a side street that wound off from beneath the steps of an official building. Mayorico seemed to want to make some response. He chose his wording more carefully than someone simply making conversation. They were to the house before he spoke again: "He doesn't cease to exist simply because you don't believe in Him."

But he was grinning. Even holy, Mayorico was an insolent little cocksucker. They entered a dingy, white-pillared, one-storied cottage. Mayorico fetched a wet sponge and a couple of lukewarm Montezuma beers. "We'll fix you up, honey, go see Cana. Good shit, there. Not cheap, but available. Got enough cash?"

The gringo nodded, licking his lips. In anticipation of the hit, he'd already searched himself, found the gold ring, which he believed was better than pesos to Cana. Mayorico moved around the airless room. An enormous dead cockroach lay in the middle of the floor. He kept stepping around it rather than doing anything else.

The door creaked and a girl came in with a sack from the mercado. Mayorico's pretty, moody daughter, Lupita. It wasn't a school day, but she wore her academy uniform, white blouse, a checkered skirt. A patina of sweat sparkled like dew on her full brown lips. She picked up the roach and threw it out the window. Mayorico pretended to spar with the gringo. "I thought he had bought it, this guy," he explained to her, though by then she was impervious to the sight of cankered narcotraficante loyalists and their perplexing compulsions.

"He will," said Lupita. "You don't see too many old junkies; notice that? For me, I don't get it. Trade anything, trade your house, your car, even trade your body. But trade your life? How does that make any sense? What good is the high if there's no life?"

She began to stir a pot of beans and Ball Park salchiches. She spoke to the gringo with sensual self-confidence: "You were very handsome when you first came around. I was twelve. I had a crush on you. Now, you have become very ugly."

"She's incorrigible", explained Mayorico with his vivid, half-caste version of a smile.

Lupita shrugged. "Adam looked into a pond, he saw his own reflection. I wonder if he liked what he saw?"

A fever came over the gringo, he nearly fainted. A lot of memory returned. It was almost like throwing up. He came back to himself in a sudden download. He rose, bracing himself against an iron bedstead. "Where are you going?" said Mayorico, frowning suddenly. "You haven't even drank your beer."

"I'm going home now."

Mayorico saw his chance for obtaining a free cut of the impending deal evaporate. "You know how to get there?" he asked, skeptically.

"I think so."

The gringo paused at the sink. He had an afterthought. "Thank you," he said to Lupita, handing her the spiral ring. She examined it, shrugged again, pressed it against her breast inside a pocket that bore the insignia of the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

He wandered among the tortilla stands, stalls that sold fruit-juice and dirty magazines, whose proprietors sat back on chair legs and contemplated lottery tickets as if they were a game of skill. Far off, the peak of Orizaba was lost in the haze of the advancing summer. Meringue music leaked from a radio, and after a while, he paused in front of his own miserable doorway. At the alley mouth, a stringy-haired Indian woman sat on a straw mat, taking coins.

Within the sala, his son considered him with a washed-out face and a listless glare. He didn't look happy to see his father, who'd been gone two days; a common enough occurrence. The kid obviously couldn't care less. He was hardened already; even at four he was too smart for the bullshit. 'If Daddy's working all the time, how come we don't ever have any money?' His Spanish was flawless.

Nicki stood behind him clutching at her little gold cross instinctively, protectively. Her hand was clearly injured from where he'd twisted off the ring. She had it trussed up in an old diaper; bandages were expensive, and besides, since she didn't speak the language, she rarely went out. He stood there stupidly. She still looked strange to him with her close-cropped hair. When they'd first come down, it had done a dramatic cascade to the crook in her back. Now, with apartment water iffy half the time, washing it had become too much of a luxury. Too bad; it was her most remarkable feature. "You prick," she said. "You sold my ring for junk, didn't you?"

He was reminded of a street proverb invented to explain the various local revolutions. The violence continues after the cause is forgotten. "You prick", she said again. Her voice was drained to flatness, too pained to be emotional. There was no real heart behind it. Unlike Mayorico, she was as good as her dogma. Despite his best efforts, she couldn't hate him. She didn't have it in her. He'd once mistaken this grace for naiveté. Now that she'd lost the last traces of naiveté, the grace was raw and exposed. He knew that in such an environment, that would begin to go next. Like when a starving person uses up the fat cache and begins to digest the muscle. It was an ancient and bloody land, much worse than the most paranoid tourist realized.

She vanished into the bedroom. A dirty birdcage and sickly sweet emanations from a pair of overly ripe melons soon made the sala beyond tolerance. He stepped outside, where the Indian woman sat stoically, still as a statue. Beneath her rug, she fiddled with a rosary.

He sat on the porch stoop and watched her. A devout and pious atheist, he'd engaged his own search for redemption, for reasons to believe. 'How about 'love your neighbor as yourself;' Nicki had once offered, 'that's common sense, that's got nothing to do with religion...' He exhaled and spat, thickly, into dust. Without heroin, life tends to look like an endless vacancy. But he was getting older, and Lupita was right; you didn't have any old junkies. You either died or couldn't hack the game any more. For things that went wrong, the paybacks were insane, as befit the players. They'd been known to slit the throats of your children, reach inside and rip their tongues out downward while you were strapped to a chair and forced to watch. It was called La Corbata, The Necktie, because of how their tongues looked afterwards. It got your attention.

Mayorico appeared, wobbling slightly. He was now wearing a straw hat tilted giddily over his greasy brow. He'd drunk both the Montezumas, and a few more besides. He sat down as if to rest from the weight of the sun. He lit a cigarette and gave one to the gringo, fixing him in a long, lingering gaze.

The gringo's nerves were shot. Having this unshaven Mexican breathing on him, staring at him, didn't help. But it was one of the countless nonessentials you had simply to get used to about Mexico; they stared at you unabashedly. Culturally, they didn't see it as an invasion of private space. It was how they sized you up.

Mayorico rummaged through his tight trousers. He held out the spiral ring. "Lupita says for me to give this back. She says it's bad karma if she keeps it. Something for nothing. Crazy talk, that kid. Wonder where she picks it up? Sometimes you don't wait for karma to happen. Sometimes you give it a little nudge."

"No shit," said the gringo. "But she's wrong. It was something for something." He took it anyway.

In the bedroom, Nicki lay on the bed, sleeping. His son was awake, curled up alongside her. He kissed the boy's cold brow. The skin was so pale it was transparent, like a guppy or a river insect. He laid the ring carefully by Nicki's head so that she'd see it first thing when she woke up. Depending on how long she slept, she’d see some bus tickets beside it. He tiptoed back to the door.

Outside, Mayorico still sat on the stoop. He hissed in venom, holding his cigarette between delicate fingers. They tapered like a woman's and looked useless. The gringo's own cigarette, fuming into ash, lay in the dust unsmoked.

Mayorico had a solemn, dark-skinned Mary tattooed onto his forearm. The gringo tried to make small-talk, a simple show of politesse: "That looks a little like Lupita, doesn't it?" Mayorico beamed, finally sincere. In fact, it was the Virgin of Guadalupe, after whom the child had been named. The comparison was an apt one, though not necessarily a compliment. The tattoo showed a strange paradox; a virgin without innocence.

An interesting phenomenon, unmentioned in the secular histories of Mexico, was the miracle of Guadalupe. The Mother of God had appeared to Juan Diego as a mirage upon a hillside in 1561, and caused such a massive conversion of the native population that Catholicism effectively became an Indian religion, which it had remained ever since. The image of the Virgin was everywhere, on men's forearms, on cigar boxes, in alley graffiti, dangling from taxicab rearviews; it's been called the unofficial flag of Mexico. Colloquially, she was called La Morenita, Little Darkling. The people loved her because she was, without question, one of them. You could see the same brown face and raven-black hair mirrored in a thousand passing schoolgirls, peasant girls, shop girls, skipping, laughing, pouting girls, girls so pretty, so exquisitely pretty, so compulsively pretty that they might have existed only within a dream.

This story has not been rated yet. Login to review this story.