Like many budding photographers, my first monumental failures were of the moon. No matter how exotic any phase of the cycle looks in person—as a waning half-circle or a waxing crescent or in full ruddy eclipse—the image that appears in a snapshot never comes close to capturing the sensuous splendor of the genuine moon suspended over your head. A moon in pixels or emulsion looks ridiculous; it’s the beam of a flashlight in an infinite black forest.

Sunsets don’t fare much better. On my first day of Fundamental Imaging at CCS, we were given a weeklong assignment: Seven sunsets, one photo for each night. We were tasked with making them as aesthetically presentable as possible under the various light baths that natural conditions would provide. Most of us—myself included—were seeking careers in the arts, and like the others, I tackled the project with naïve earnestness. I waited patiently through cold and cloudy afternoons, breathing autumn billows onto my Rebel T3i, waiting for a glimpse of a sinking sun. On days when the sky never cleared, I focused my lenses on powdery grey striations and horizons the color of oatmeal; I focused on compositions. On days when nature provided a full pageantry of russet reds and harvest oranges, I took dozens of shots, trying to capture the pomp of a sky broadcasting another day’s demise and reflecting itself in fires of stained glass on lakes and dolloped clouds. I was moderately proud of the results, and so, apparently, was everyone else in class—there was a lot of smugness as we turned in our portfolios, followed by righteous annoyance when the teacher dumped them all in the bin by his desk.

“Sunsets suck,” he announced. “Now that you’ve gotten them out of your system, I don’t want to see another fucking sunset in my classroom for the rest of the semester.”

My professional life is now ten years deep. Across that span I’ve been called upon twice to use sunsets as photographic backdrop: Once for a retirement villa brochure and once in an advertisement for a Mazda 3 Hatchback that wound up on a billboard overlooking the Lodge. It was maudlin, heavy-handed, commercial rubbish, unrelated to the natural phenomenon of setting suns, and technical sleight-of-hand cannot change that. Forget sunsets and definitely forget the moon—no lens or Lightroom slider can produce a faithful representation of the moon’s mystery, intangibles that are far removed from details of craters or mountain ranges. For an art photographer, the moon remains inaccessible; its essence—the power of its inspiration—is immune to us all, amateur or seasoned pro.

Last month, I discovered that this holds equally true for northern lights. I was in Gaylord photographing some rich kid’s wedding, and late that night, a splendid aurora blew up over the lake; a magical green grail with ghost tentacles twisting and writhing through the sky. First-hand, the lapping display was immense and exhilarating, but the raw photos I took were useless. I had to feed them post-processing steroids before they became even vaguely coherent, patching in the contrast and the clarity and, by toggling the colors, the vibrancy.

That at its core is dishonest; hardly a feather for the cap of someone who believes (as I do) in the sanctity of art as stripped-down, unretouched reality.

That’s why for me, people have always made better subjects. In any portrait, on the street or in the studio, I look for a congruent exposition of private souls, an individual moment snatched from a speeding train, always with the understanding that even if my narrative is compressed into the merest fraction of a second, that moment must portray something profound. Real lives are composites, and I have learned to measure my success by how faithfully I can reflect an instant in the flux.

I’d gotten fairly adept at it, too, while finding outlets that paid the rent. When the price was right—never less than $3000—I did weddings, and I regularly freelanced to Cityscape, a magazine catering to Detroit’s moneyed elite. Along with tilting strobes and a camera kit—my mechanic’s toolbox, my physician’s black bag, my lifeline—I was welcomed into the homes and halls of the strange and wealthy people who populated a rarified nightlife, and they seemed to appreciate the titillating aura in which I was able to capture them; more than I did, for sure.

I was also an occasional visitor to another, somewhat darker world, sometimes professionally and sometimes not, but always with a surreptitious ogle. This was the realm of Detroit’s hardcore underground: Techno raves with luminescent dance floors, bizarre acts by edgy artists, and everywhere, a collation of glittery, weird and hedonistic costumes often swamped amid drug-fueled cuddle puddles.

My girlfriend Jenny was a huge fan of both indie dance and neoteric art, and in fact, spent her prosaic working hours as a development manager for the Rolf Witt Testamentary Foundation, streamlining funding to some of Detroit’s most fiery fringe artists. She loved high caliber pop-up parties, and occasionally arranged with the hosts to have me take photographs for their web sites, although more often than not they were camera-free events since guests showed a lot of skin and wanted their privacy and personal space protected. Like Jenny, many people attending these shows had professional lives, so at the door, dutiful security guards would use colorful stickers to cover everybody’s cell phone cameras. Jenny—generally prepared to walk her wild side after dark—actually preferred the raves where I was not allowed to work since there was less chance that her employer might turn up Facebook shots of her ass cheeks in an open-back leather skirt.

She offered up another reason too: “Come on, Shane—don’t you think people hanging out without looking at their fucking phones non-stop is kind of great?”

I did, but I preferred places where I could gawp through a lens, probing, insinuating, finding in the human herd unique configurations, singular hues and striking blends, smudging my nose against a steamy window.

And it was at one such rave, about a year after the aurora by the lake, that I took the image on which the rest of this narrative hangs.

The party—held on an unseasonable warm Friday night in April—happened inside ‘Salvaje’, a refitted, distinctly repurposed Catholic church on the city’s Southwest side. The blue-collar neighborhood, mostly Hispanic, thought the re-do was blasphemy, but in fact, a secular revival had saved an empty church from the wrecking ball. Not only that, but nationally, the venue was now better known as a den of reggae, breakbeat, Italo disco and underground hip-hop than it had ever been as a house of God. Sacrilege or not, I thought it was impossible on some level not to appreciate the building’s polyphonous, cacophonous makeover, a stunning fusion of vintage and contemporary still guarded by two brass angels that remained on the fence posts.

Like most of these events, this one was without a definable purpose or calendar reference, advertised as ‘a retrofuturist party for true heads with a mind-bending lineup of intergalactically inclined DJs playing house, soul, techno and acid.’ It was dubbed ‘Freakopolis’ and this time, the proprietor called me directly, promising in his twitchy, splattery street patois, “It’s gonna be Lit City 9001, skippy, and that’s a guarantee. Bring Jenny and get your brain licked and also, bring your third eye so we can open up the city to what we’re doing.”

So we went, Jenny in a black pencil mini, wrapped in mesh-panel leggings with a silk blouse open to her navel; me in a patched up old denim jacket and jeans. I was a stand-out amid the the straps and chaps of full-on fetish Goths, but that was fine—I’d been engaged as an observer and I was being paid as an observer, and observe I did.

We arrived at ten, and instantly, the party enveloped us. It spread across zoned spaces, each with a unique purpose: There was a dance floor with DJ booth topped by geometric installations, a bar overflowing with the marshy heat of dozens of close bodies and a hall draped in streamers and illuminated by black lights where people were chilling in clots on industrial-punk furniture with strange, provocative lines. Thunders of noise came from one of the more advanced set-ups in the city; Eastern Acoustic Works Avalon loudspeakers behind which hung vivid projection screens and a state-of-the-art Platinum Elation lighting system—a post-studio experience, the flyer had sworn, that would collapse the space between sound and vision.

I came equipped with the armor and expertise needed for this sensory onslaught—a bumped ISO on my prized Canon 5D Mark and shutter speeds ranging from an eighth to a hundredth. I measured focal lengths and crop factors and adjusted parameters to accommodate the swarms of moving bodies; I covered the upstairs like I was sweeping a field for mines, and when the noise became unbearable, Jenny and I moved to the quieter basement, tonight dubbed ‘The Dungeon’.

There, a chain-link fence surrounded a woman engaged in bizarre performance shtick, writhing naked beneath a single spotlight, ripping nails from a piece of wood while reciting a maniacal, absurdist poem about the soft wood of soiled souls and how the suppurating wounds left by the spikes must be purged in the cauldron of Purgatory. It was a perfect incantation for an old Catholic church, and also for a rapt audience who stood dumbstruck and mesmerized by the nonsense. They were more interesting that she was, and I took a number of shots into the bower of shadowy faces, and after that, Jenny and I threw back a few shots and left.

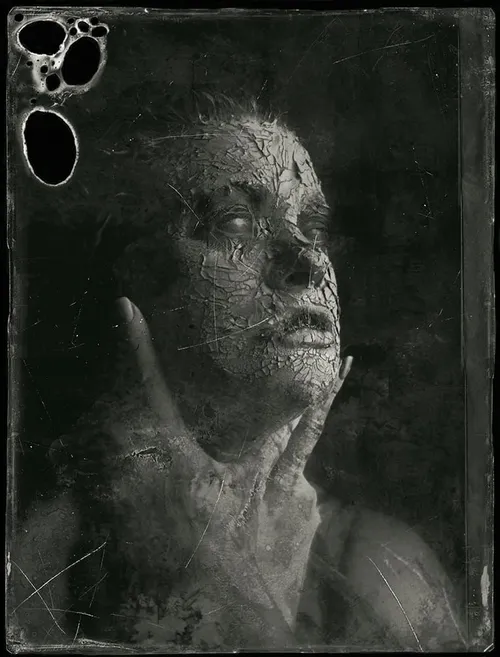

It was not until the following day when I was examining my work on the computer that I came across a singular image—one photograph of the hundreds I took where the balance of mysterious characters was perfect, a Doré composition beneath Rembrandt light. I would have seen it as a prizewinner for that alone, but what was most striking to me was the lone, illuminated face just to the left of center emerging from the teeming darkness. At the time I took the shot, I hadn’t even noticed it.

It was a young woman caught in a nanosecond of insular and fugitive light—the divine discharge on which photography depends. But it seemed to have no external source; not the nearby spotlight or my flash gun or my diffuser. It did not look like reflected radiance anyway; the face showed a glacial glow that seemed to come from inside. A flicker of intransigence or disquiet? Foreboding or insolence? Whatever it was, it defied identification.

And yet the more I looked at the cold, inadvertent halo, the more I wanted to identify it. More than that, I want to capture it again, in proper lighting, in a different ambience—in an atmosphere that I myself created.

But that would be a problem, of course—I had no idea who she was. And there was only a single way approach it: I enlarged the shot to isolate the face. Inflated, it was impossible not to be jarred by the precocious hardness in the eyes, which drew from some buried annex within. Someone else would recognize her, I thought, so I sent copies around to the handful of people I knew had been at the party. I engaged Jenny in the same search, since she knew more of the guests than I did.

I tried to temper a fever pitch around Jenny, but as one by one our contacts shrugged, it began to seriously torment me. Only a couple of our friends could remember seeing her and no one could identify her. I examined all my pictures and found her in a few more—she was lithe, almost feline, dressed in a scoop-neck man’s tee, a layered taffeta skirt and knee high socks—but none of these shots were as compelling as the first, in which her face seemed to emerge from the magic and mystery of metaphysics.

In the end, after all available pathways came up empty, I took the original photograph to the studio and had it blown up into a two-by-three-foot poster. I mounted it on foam board and hung it prominently in the front room of our Indian Village apartment.

Of itself, this was not odd—our place was festooned with photos, my favorites and hers. There was a shot of two Detroit firefighters standing before a burning tenement, each looking in opposite directions and neither at the fire; it had taken first place in a contest sponsored by Monovisions Magazine. There was a sharply focused tip jar on a greasy-spoon counter with a softly focused short order cook laboring behind it. In one, a businessman stepped over a drunk on a city street and in another, a crow perched ominously on a One Way sign.

But I hung the glowing girl directly above our mantle, and this made it a focal point, impossible to ignore when you first came in. When Jenny came home from work, she stood beneath the poster for a long moment before saying, “Is this a test? To see if my ability to indulge a preoccupation has limits?”

“Of course not. Sooner or later, someone who comes over will know who she is. The circle around here is really not that big.”

“Okay,” she said warily and left it alone.

With her balanced pragmatism and calm good sense, Jenny was good contrast to me: She was my mild, rational anchor and my confidant. We’ve shared our space in Indian Village for four years and I saw no reason to suppose that there might be an end in sight. But it was evident to her that a quick storm was blasting through my heart—hardly a crush, but certainly, a fixation that from her vantage may have seemed as edging on the unhealthy. She was not jealous as much as perplexed and not exactly sure how to feed this sudden, inexplicable hunger. We were in love—neither of us doubted it, and I could convince her of an idealistic quest from a creative core, but in the spirit of love and consequent good faith, I could not deny that it came from a hole deeper than she—or art—could fill.

But it was Jenny herself who came to me two weeks after the party, a week after I’d hung the photo above the mantel, to say, “Well, I suppose you’ll be glad to hear this, Shane. I found your girl. She works at Veganomics waiting tables.”

“That little organic café on Agnes? Right around the corner this whole time? Are you sure?”

“It’s her,” she said guardedly, crooking her finger at the poster. “But let me say this; in person, she doesn’t look like that. She’s a kid—not even eighteen, I wouldn’t think. That’s why I asked her if she was at Salvaje that night… So I could be sure.”

“Wow. So much thanks, I can’t express it. Did you get a name?”

“Anna,” Jenny said, nudging it into European softness by pronouncing the ‘An’ like ‘on’.

“I have to go talk to her. Like, tomorrow? You understand that, right? To see if she’ll agree to a private shoot?”

“Hang on, Shane. I have to say this too: I got a weird read from her. A damage vibe, you know; like a mooring is torn free, some rupture under the surface. I’m only being honest here: I’m not sure approaching her is a good idea, especially with a proposition about filming her privately. She seems super reserved; that’s how she comes across. The floating head in your fantasy poster is nothing close to the real-time person I saw.”

“That’s sort of my whole point, Jenny. The challenge, always—to capture the genuine person, to draw out essence.”

“Detached people don’t always want a stranger drawing them out, though. They won’t all sign the release.”

“I know. But I can name a few people who are proud to let their freak flags fly on Friday and then look totally different on Monday morning. I won’t know if I don’t ask. You can come with me and vouch for my intentions. I’d offer her a generous modeling fee; I pay them all the time.”

“Not like this.”

I hesitated, though not for long: “Maybe. But this is me, Jenny—an invasive species. I need to see for myself. Please come with me; I trust you absolutely, and if it doesn’t seem kosher, if she’s allergic to compliments and immune to money, we’ll pull anchor and head home.”

Against Jenny’s better judgment (I think), she finally agreed. Her reasons were complex, founded perhaps in the idea that Anna might be able to use a cash infusion—slinging vegan burgers couldn’t pay much. Not only that, but Jenny had seen that Anna was a striking girl who might actually relish an opportunity to start a professional modeling portfolio. Veganomics didn’t lend itself to résumé fodder.

But what Anna also knew is that since my thirtieth birthday the previous year I’d grown increasingly dissatisfied with photography as ‘my’ medium. Because we’d spoken about it—usually after knocking back multiple tequilas—she also knew that I’d been considering dumping gasoline over my career, striking a match and saying ‘whoosh.’ Perhaps she was hoping that if Anna agreed to a session, I might be able to regain my mastery; some sense that my creative pursuit—shining lights into the obscurity of lives not my own—was underscored by aesthetic purity.

That my preoccupation with the photo—the otherworldly and eerily beautiful face rising like phosphorescence from the shaded world of leather bustiers and chainmail halters—might come from a stranger place? Did she suspect that as well? Perhaps; inevitably, my storms spill over onto her. And truthfully, this was something we did not discuss, even after tequila.

So we went to Veganomics the following day, calling ahead to ask if Anna was working and requesting a table in her section.

The place was small; a dozen tables flanked by a smoothie bar and bright walls studded with stock photos of vegetables and one massive panorama of Detroit as seen from Windsor. And when Anna emerged from the rear through an avocado-colored swinging door, I saw everything that Jenny has seen in a single imperious instant.

She was more colorful than she looked in the photo—her eyes were hazel and her fair hair feathered into a bleeding-red ombré. In person, she was very pretty, but unobtrusively so, and much smaller than she looked as a disembodied face above the leather-daddy hulks and shadowy cyber punks. But to Jenny’s point, an odd vacancy hovered around her and it was perceptible immediately—a vacillating fog that seemed to suspend her in space, just like in the photograph.

We were here and there was no backing out (of a meal at least), and Anna approached us with an odd, oblique expression, clearly baffled that anybody would request her. Jenny spoke first: “Do you remember me? I was in for carry-out yesterday and I asked you if you were at ‘Freakopolis’ a few weeks ago.”

Her tone was perfunctory; a worker with another wooden piece to assemble as it moved down the conveyor belt. “I remember,” she said blandly.

“Well, great. I’m Jenny, by the way, and this is my partner, Shane.”

She said, “Hi,” while pointing at her name plate for identification.

“Did you have fun at Salvaje?” I asked.

“Not really,” she shrugged. “I’m sort of into interpretive dance, and one of the customers said there was going to be some kind of performance artist there. He gave me a freebie ticket. I went, but wasn’t my scene, so I left.”

She shrugged again and proceeded to whittle away at her obligatory block of wood, explaining the daily special—Seitan stir fry with brown rice and sesame broccoli.

Jenny was all air and sunshine: “What’s your most popular item, Anna?”

“Probably yam chips,” she answered without making eye contact, without interest.

“Let’s start with those, then we’ll decide.”

Anna moved on to other blocks of wood, not even writing the order down. Jenny had called her damaged, but to me, a word that more precisely captured her was ‘self-contained.’ Still, Jenny was absolutely correct about the vibe—it came across as pinched energy and an odd detachment of spirit. Within her, there was an unnamable compression, and far from putting me off, I became all that much more fascinated.

“And?” Jenny asked me shortly.

“I’m sorry, but I see the same primal thing here that I did in the club. Identical. Maybe even stronger.”

“You see how young she is?”

“Sure. But there’s nothing creepshow about what I’m proposing. I want to make her an offer.”

“Then do it.”

When Anna returned with the yam chips, I pulled my cell phone and flipped to the picture. I held it up and said, “Jenny told me you worked here and I wanted to show you something.”

She put the chips in the center of the table and took the phone with a puzzled frown. It took her a moment to make out what she was seeing: Herself. I can’t know her private interpretation, but I was comfortable with my own: A numinous crystal rising from a dark forest of instigators and freaks.

I said, “Look, Anna—I was hired to film the event and this is the best picture I took all night. Seriously. You have a unique, very photogenic look.” I poured syrup over it: “A white crocus in the spring as it dislodges snow.”

Now she made eye contact—with Jenny, not me, considering her with a suspicious squint.

Jenny’s returned a nervous smile and glanced at me out of the corner of her eye.

I went on: “I’d love to photograph you in a professional studio instead of a smoky nightclub. I’d like to catch the real you in real light. Ambient light. A couple hours work for good pay.”

“I’m not interested,” she said flatly.

I’d been semi-prepared for that. “Google me before you decide absolutely. I’ll give you a card with my website listed; go see for yourself the kind of work I do. It’s art photography, nothing sketchy. A hundred an hour is a standard modeling fee; I’d offer you five hundred for a two-hour shoot at any location you name.”

“No thanks,” she said, and the moment hung over us like a freezing moon until my inestimably valuable co-pilot broke it by ordering the smothered Seitan.

Anna walked away, and pointedly ignored us until the food arrived, at which point she dropped it mechanically and said nothing more until she brought the check. I paid with my AmEx, leaving a fifty-dollar cash tip on a thirty-dollar bill. I also left a business card inside the presenter; on the back, I’d written, ‘Anna: I can go a thousand dollars for a single photo shoot, in any location where you feel comfortable.’

When she returned, her posture was rigid, like having to repeat herself as a parent to a stubborn child was not something she’d signed up to do, not part of the job description.

“I’ll pass,” she said abruptly, and this time she looked at me directly; when I opened the check presenter, my business card remained where I’d left it.

When Jenny and I were outdoors on the wet pavement, I said, “At least she took the fifty. If nothing else, I assume that means I bought the rights to the picture over the mantel.”

“I'm sorry it didn’t come together as you were hoping,” Jenny replied, and I knew that she meant it—as a partner, she was accommodatingly sweet, without a told-ya-so bone in her body.

Nor was I likely to be told: The following day I went back to Veganomics with an envelope for Anna. Inside were copies of number of my photographs, all prize-winners, along with some articles written about me locally. I included a brief note. It said:

‘Anna, I apologize for springing this on you so suddenly yesterday. It wasn’t fair. I am serious about the offer; you have striking presence that I’d love to capture in portrait. I assure you that I’m above board and legit and I can go $1500 for the two hours, anywhere you name, anywhere you’d feel safe, even your home. - Shane’

Anna was not working that afternoon and I asked a tall black woman behind the register if she had an employee box or locker space—we’d been in the day before, I said, and Anna had asked to see some examples of my work. “I told her I’d leave them for her.”

“She has a slot for her time card,” the woman answered. “I guess I could stuff it in there.”

So I left the pictures and waited. When a handful of days passed without a word, I began to understand that there were bigger things at work; within Anna, perhaps, but certainly within me—a desperate reaching.

And I collided with a new and equally insidious truth: The power of the image above the mantel worked on me as a viewer, not as a photographer. Anyone could have taken that shot with any crude antique from eBay; it was purely an accident, unrelated to the eye I’d spent ten years honing. It was art that belonged to the fourth wall, not to the artist. I didn’t like to be reminded of it, so I took down the poster and replaced it with the original piece depicting a beautiful black youth in a scarf turban and dreads belting out a tune during a jazz fest in Hart Plaza. I exhaled and gave up hope that Anna would call.

And then she called.

It was ten-thirty on Tuesday night when I was puttering with retouching software on the computer and Jenny was already asleep. My phone vibrated: “This is Anna from Veganomics.”

“Hi, Anna. Everything okay? I’m really glad it’s you.”

“I’ll do it,” she said abruptly. “Your shoot. Tomorrow; I get off work at eight. But the only way I’ll do it is if you come here to the flat. I don’t want to go anywhere there might be other people around.”

“That’s fine, Anna—that works out perfectly for me. If you feel comfortable and safe, the photos will be all that much more spontaneous. That’s what I’m after. I...”

She cut me off, gave me a nearby address on Kercheval, and then hung up.

I told Jenny immediately, but I didn’t tell her the entire story, then or ever; she thought the five hundred I’d offered originally was preposterous—fifteen hundred would have been inexplicable, bordering on unforgivable. So I was sly and secretive and spent the night restless and quietly ashamed; in any rational assessment the money I withdrew was ours and I did not take it from our joint checking account where it would have been noticed—I took it from our high-yield APY.

Anna lived in a rust-colored building on a strip of the avenue dominated by boarded storefronts, failing Coney joints and mucky quick-fix stalls. It was only about six blocks from our oasis in Indian Village, a world removed this tyranny of foreclosures and burned husks overdue for demolition. For Anna, the cash in the bank envelope would probably cover three months’ rent.

On Wednesday at nine, I was buzzed into a rank vestibule where scrawny cats skittered like rabbits; I climbed to the fourth-floor Section 8 walk-up and found the door propped open. It was the building’s top floor, but inside, there were subterranean scents and curdled cellar atmospheres. The flat was barely lit, but shortly, things shuddered into shape; a long room, both cramped and empty, flecked with stark furniture that looked like throwaways from someone’s basement. The walls were bare, without so much as a Mod Podge paint-by-numbers as art.

Anna was in the far end, leaning on a refrigerator whose door was also open, eating out of a cardboard container and lit by the tiny refrigerator bulb. Her legs and feet were bare; she was in underwear and the same sleeveless t-shirt she’d worn to the club.

She didn’t speak and neither did I, and in the enveloping silence, I pulled my camera from the case and slapped on the compact lens I use for street photography, vital for the exposition of secrets and ideal for harsh environments with delicate subjects.

I moved as breathlessly as I could. I took a dozen of shots, searching in the trivial and mundane for an angle, a spatial composition, a candid exhalation. There was no sound but the shutter and the whirr of the fan from the refrigerator, shattered suddenly by Anna’s voice:

“Do you want me to take off my top?” she asked.

“Do you normally take it off while you’re eating?”

“No.”

“Do you want to take off your top?”

“Not really.”

“Well then, of course not. Is that what you think I’m here for?”

“I don’t know what else.”

“Sure you do. I’ve been straight with you.”

She shrugged and the mood evaporated. She began to putter, putting away condiments, washing a lone, lonely dish. I withdrew deeper into the flat and sat on a tattered couch. After a minute, I said, “Maybe I didn’t really explain it, though. I’m a concept photographer; it’s what I do. You’re young; you might not be familiar with the term—I didn’t really think of that. It means that I try to find art in the abstract. I think you have a look that is wildly interesting. Inside a club is one thing, but I wanted you in a natural setting, not posing, just going through your routine. You don’t have to do anything other than you normally would—operate inside your own rhythms.”

“You paid fifteen hundred dollars to film a chick eating leftovers?”

Well, finding something sublime inside that was my business: “Maybe I did; I won’t know until I see the proofs. That’s the way this works. Pixels are cheap.”

“Whatever, dude.”

“Call me Shane,” I urged, but she didn’t; she reached for the heel end of her sandwich and finished it.

I moved as far back in the flat as I could and went over the shots I’d taken so far, and guess what I saw? A chick eating leftovers.

When she stepped from the kitchen I said softly, “So dinner is over. It’s a typical Wednesday night. You’re home from work, maybe you have to work again in the morning. What do you do now?”

“Listen to music and go to bed.”

“Okay, so that’s perfect, Anna. Put on your favorite tunes and let yourself get swept away by them. Be chill, be abandoned; get lost. Forget about me; be about you.”

She nodded, shook her head, and when she leaned over to plug her phone into Bluetooth speakers I noticed a spread of fierce bruises on both of her shoulders, hinting at private moments unrelated to this one. A different garment would have hidden them, so she either wanted them to show them or didn’t care.

The thrum of a bass and a soft cymbal lifted to the ceiling; it was familiar, but it took me a second to identify ‘The Trinity Sessions’ and a cover of the old Hank Williams classic, ‘I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry.’ Chills ran through me as Margo Timmins’ crystalline voice rose through the hollow halls of St. Trinity in Toronto, an echo in a sanctuary. When the delicate, impossibly immersive guitar soloed, Anna began to sway back and forth in front of the window, her eyes closed.

The lone illumination, filtered through filthy panes, came from a street lamp outside. Her rhythm was unerring; a soulful displacing of space sculpted in dirty light. Dampness appeared on her t-shirt like raindrops. So it grew from a session to a séance, and as I framed the shots, she seemed supremely comfortable and bleakly beautiful—this was her skin, bruised and perspiring, and I had a sudden, incongruent memory of being a child inside my own room, content and safe through hours of leisure, considering my things; my science books, my mounted Saba sabre, my posters, the view from my window, ever changing yet always the same.

The dirge ended and another one came up, this one even more poignant: ‘Blue Moon’ from the same St. Trinity session. Anna’s surrender, passing from a liquid to a near vaporous state, feral and faintly cat-like, blessed her with sublime distraction, the thing I’d been hoping for. Not frustration or fear, but capitulation to helplessness. It was so powerful that tears began to run down my cheeks, an inadvertent and unexpected release, like a night emission. Spontaneous was what I wanted and that’s what I got, keen and telling, from myself. I’d asked her to pretend like I wasn’t there and she’d slipped into a place where I didn’t even exist.

I collected myself, reviewed the images, and what I saw in the display window was all wrong. Anna’s bewitching motion was fundamental to any real-time portrait; a reflex camera was useless. But even a high-def video would never have been able to duplicate the gritty gloss on her mottled skin; the precise counterpoint of beauty and blemish, nor—I was sure—would film have reproduced with any accuracy her unearthly carnality, the graceful sweep of cold thin limbs, the shades of private wantonness, the stopping and starting of her breathing; any attempt to record this would have produced distortions worse than a still shot.

And yet, this was my channel—a form of art that causes you to miss the very thing you’re after, in real-time, just as it is occurring.

I saw myself, perhaps as Anna had seen herself in my viewfinder, and it took a second for the mists to clear. I was standing outside a celestial world and I had been here before; it is territory that no camera can penetrate. Before me, Anna was an object dangling in defiance of summary or reduction. The gulf between us was wider than a room or a universe of rooms and a photo session was inexpressibly unfair to us both. As a burden, doubt is insidious: Unlike the hundreds of thousands of space miles to the moon, or the aurora in the upper atmosphere, the distance between Anna and I was unfathomable, without words or limits.

So beneath the profundity of that realization, I stopped meddling.

The answer had come to me, so basic that any child could have offered it instantly, although to an adult with a perceived purpose, it took the consensus of an entire psyche. How infinitely more useful it would have been for me had I simply appreciated the aurora as it happened and not struggled vainly to photograph it, only to fail, and by professional necessity, to fake what I’d seen later.

I took the lesson now and watched Anna move like I should have watched the volatile sky above Crystal Lake: In quiet awe, without a camera, without a hunger to take anything away or to revive a spark long after it has been extinguished. She vacillated through suspended dreams, moving for herself, for the furrows of music, for healing blue light from a pearl beyond the overcast, for her small room, for anything except a lens. She became Salvaje’s promise—collapsed space between sound and vision.

A theory in physics suggests that observing a phenomenon inevitably changes it; checking a tire’s pressure, for example, requires an instrument that alters the pressure. Anything I did in that moment—the bite of a shutter, the raising of an elbow—would have been altered the moment. How much better to sit unobtrusively and process the essence, absorb the beauty, acknowledge the potency of such a rare sight without clutching a machine—a device that would, by necessity, change it?

I saw in a sudden, explosive download that I’d already wrung all the art from her I could; it was on matte and foam board and hung in my apartment. And it had been an accident. I set the Canon tenderly, wistfully back inside the leather case the bag, snapped it shut, and I did not open it again. Ever.

And in this way, on a chilly night in the late spring, Anna became what she represented, the alpha and omega of my story as a photographer. I left her flat before the song was over, the bank envelope set on top of the camera case. When she broke her own spell, calling out sharply to say I’d forgotten my equipment, I answered, “No I didn’t.”

Jenny had been right: I had regained a sense of mastery—not my craft, but of my eye, of an adolescent moon; Anna was a cold glow in a black forest, as immune to reproduction as any sky phenomenon.

Of course, for this analogy to be accurate, it would have to be in a world where I never looked up and saw the moon, even unfettered by contraptions or purpose, because after that night, I never saw Anna again. I have no idea what she did with the camera, although I retain a slight fond hope that she learned how to use it, and with more account than I ever could. Perhaps she found a single picture she liked among the dozens on the memory card and had it blown up to poster size to hang on her barren wall.

In the weeks, then months, then years ahead, the afterimage—Anna’s pulse to music beyond human frequency—would be sequestered within my heart in the place I reserve for unique manifestations in my life’s experiences. These are sounds and sights that despite their significance, remain unaccounted for and unresolved. Many sudden deaths, many lost friendships, many childhood vistas and many bittersweet and unutterably melancholy songs are also residing there, shifting in the moonlight. I hold each of them dearly and tightly.

But in the world of creative expression, those dusty relics get restless. Sometimes they petition the spirit for a return to daylight, even briefly. On a rare occasion I will listen to those songs again, consider my ghosts and allow myself the luxury of sadness.

After I gave up photography, I took a serious run at writing. This outlet, I’ve found, allows me freer reign with moods and sensations; the chance to exploit another paradox of physics in which light is simultaneously a particle and a wave. I’ve learned, like Anna knew spontaneously, how to rely on interior light: My characters are particles and my choice of words is a laving lake intended to create waves of emotion that do not wash toward shore but away from it.

This story is my first attempt to do that. My success or failure? I leave that to the reader.

This story has not been rated yet. Login to review this story.